This entry summarizes a series of 1970s mainframe games that have been so lost we don't even have screenshots.

Before posting this entry, I scoured available books, magazines, web sites (including those archived), and message boards. I also asked several dozen PLATO authors, administrators, and former CRPG Addict contributors--everyone I could find--for any additional recollections about the games. I stopped only when I was confident there was nothing left to learn. If you have any new or conflicting information about any of the games below, I welcome your comments below or an e-mail to crpgaddict@gmail.com. I will update the information below with any new material discovered. However, please do not take it upon yourself to try to track down and contact any of the people listed here on my behalf; it is likely that I have already reached out and they either declined to respond or already told me all they could.

Most of the games listed below were written in a language called TUTOR for the PLATO educational mainframe hosted by the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. (Some of the authors of these games come from schools that had PLATO links, like Purdue University, Iowa State University, and Indiana University.) Many of the games written on this system have been preserved and are playable today at Cyber1. Games that are not lost, and that I've already covered, include The Dungeon (1975), The Game of Dungeons (1975), Orthanc (1975), Moria (1975), Oubliette (1977), Swords and Sorcery (1978), Avatar (1979), and Camelot (1982).

Students began writing these games almost immediately after the first edition of Dungeons & Dragons in 1974. The developers were aware of the games being written by other students, and there was a healthy mix of cooperation and competition. It's tough to nail down specific dates, or a specific order, for some of the games because they were continuously updated throughout the 1970s and early 1980s. (Some of them, like Orthanc, even had new coding added well into the 2000s.) What is the "release year" of games developed under such circumstances? There was no distinction between "beta testing" and actual gameplay.

The other important thing to understand about these early games is that they were bootlegging computer space. In the early years, university administrators and system operators frowned upon wasting precious system resources for games (not an entirely unreasonable perspective given the number of stories I've heard about students neglecting their studies to write and play games). Authors tried to disguise their games by giving them educational-sounding names or prefixes used by the lesson spaces allotted to various university departments. pedit5 (The Dungeon) had that file name because it was created on the space allotted to the Population and Energy group. I don't know what the prefix for m199h meant, but that was almost certainly a file name, not the actual name of the game, just like almost no game in Daniel Lawrence's DND line, including Lawrence's, was actually called DND.

Many PLATO RPGs were started, deleted, re-started, and deleted again. When Reginald Rutherford's pedit5 was deleted, students re-created it as Orthanc. When Orthanc got axed, they brazenly followed up with Orthanc2. An entire series of games beginning with the word Think was chased off the system one by one and re-created. Eventually, university officials gave up and allowed the games to remain, which is why the post-1976 games are much better preserved, sometimes in multiple versions.

m199h (1976, possibly earlier)

Long offered as the legendary lost "first" PLATO CRPG, recent evidence has suggested that instead it was a remake-expansion of The Dungeon ("pedit5") of 1975. Information about the game is inconsistent, many sources drawing from a note file on PLATO written by Dirk Pellett, one of the contributors to The Game of Dungeons. It covers the history of RPGs on PLATO. He says:

It is "common knowledge" that someone created the very first dungeon simulation game in a lesson called "m199h" which was NOT created by the account director for the purpose of gamers playing games. When it was discovered, it got the axe. Unfortunately, little else is known about m199h, either the author, or what it was like, and no known copy exists.

This would seem to be the source of Brian Dear's brief mention of the game (which he accidentally calls m119h) in The Friendly Orange Glow, the basis of numerous subsequent citations.

Adding to the mythology, a Cyber1 administrator wrote in the PLATO notes files in 2011 that "m199h" was based at least partly based on a game called Monster Maze written by a Terry O'Brian on a CDC 6600. My colleague, El Explorador de RPGs, demonstrated conclusively that in fact Monster Maze was based on "pedit5."

In August 2023, I was sent some screenshots and hand-copied images from the game by a contemporary player, as documented in the link above. I now believe.

- "m199h" was the file name, but the proper name of the game was Dungeon.

- It was created in 1976 and deleted by early 1977.

- It was an expansion of The Dungeon ("pedit5") and thus not the first CRPG. It was a top-down dungeon crawler.

- The main character was a combination fighter/magic-user/cleric/thief on a mission to get enough experience points to get into the Hall of Fame.

- Its monster list included griffins, harpies, demons, dragons, deaths, wizards, werewolves, dwarves, thieves, Spirits of Christmas, vampires, dwarf wizards, medusas, cockatrices, ogres, goblins, hobgoblins, zombies, nazguls, and wraiths. Many of these shared the same graphics. There may also have been some punny monsters with names like "hisnia" and "yourgraine" (after hernia and migraine).

- Its spell list promised every spell available in the Greyhawk supplement (March 1975) the D&D rules, whereas "pedit5" only offered about a third of them. Whether all of these spells were actually programmed is uncertain; "pedit5" had listed more than actually worked, with the yet-to-be-programmed spells identified in the instructions with an asterisk.

- It introduced teleporters and chest traps.

For more information about the recent findings, see my October 2023 article. We still do not know who created it, but the file name suggests a lesson space reserved for the mathematics department.

Dungeon (1975)

Dungeon, credited to John Daleske, Gary Fritz, Jon Good, Bill Gammel, and Mark Nakada, is in some ways as much of a mystery as m199h. John Daleske is famous in PLATO circles for creating Empire when he was an Iowa State University student in 1973. Numerous game histories and PLATO histories mention him and Empire, but none of them seem to be aware of Dungeon. The game doesn't show up in Dirk Pellett's history, either. I wouldn't have known about it at all except I was trying obvious keywords in PLATO, and up popped the title screen you see below. The copyright dates show that someone visited it as late as 2004.

In any event, the game doesn't seem to be any more than the title screen. The key commands that would normally run the program or take you to the documentation do nothing.

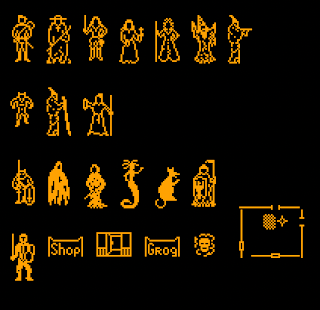

Edit from December 2021: Commenter "half" managed to inspect some more elements of the file and extract and reassemble the game's icons:

half's analysis shows files edited as early as 1977 and as late as 2004.

Dungeon (1975)

Dungeon is the only game on this list not hosted on PLATO. It was written in 1975 or 1976 by Don Daglow, then a graduate student at Claremont University Center in California, on the university's DEC PDP-10. Daglow is one of the only student developers from this era to make a career in game design and programming. He worked for Mattel (programming for Intellivision titles) in the early 1980s and Electronic Arts in the mid- to late 1980s, where he produced Stuart Smith's Adventure Construction Set (1984) and wrote a module for it. After a brief stint at Brøderbund at the end of the decade, he founded Stormfront Studios and designed the two Savage Frontier games (1991 and 1992), Neverwinter Nights (1991), and Stronghold (1993), among many non-RPGs. Later switching to more of an executive role, he oversaw the production of Pool of Radiance: Ruins of Myth Drannor (2001) and Forgotten Realms: Demon Stone (2004), again among many others.

What we know about Dungeon goes back to May 1986, when Daglow wrote an article titled "The Dark Ages of Computer Game Design" for Computer Gaming World. Amid a long discussion about the difficulties programming games on overburdened mainframes and hiding them from system administrators, he mentions his "first adventure game, which continually updated a 40 x 80 map to show what your party had seen, so excruciatingly slow as to be unplayable." In a subsequent article in the August 1988 issue, he mentions that the game had "both ranged and melee combat, lines of sight, auto-mapping, and NPCs with discrete AI."

Daglow has dropped other tidbits in a variety of interviews, but the most complete account comes from a 2015 interview with a French blogger. Here, we learn that in contrast to endless randomly-generated content of his PLATO contemporaries, Daglow designed his Dungeon more like a Dungeons & Dragons module, with both fixed encounters and "wandering monsters" on a fixed map. It was a single-player game with a party of six characters. (Multiple players could huddle around the same computer and control their own characters, but that's not the same as the multiplayer experience on PLATO, where the students could literally communicate and cooperate from different terminals.) Daglow "religiously followed all the D&D rules," which included slow combat and even slower leveling ("getting to the 4th level was a big deal"). "Graphics" were all text characters. A lot of sites, including Wikipedia, seem to rely on this interview in reporting that Daglow's line-of-sight programming included considerations of torchlight and infravision, but I'm not sure that's exactly what Daglow says in the interview. Specifically, he says that rules about lighting and infravision in D&D inspired his use of line-of-sight in the game, but not necessarily that he implemented those specific features. Nonetheless, I suppose we can extrapolate based on his claims of strict adherence to D&D rules.

Some sites continue to report Daglow's Dungeon as the "first computer role-playing game," a status that remains uncertain without more clarification of the dates of his game. But I don't get the sense from his writings and interviews that his Dungeon was played to the extent that the PLATO games were played. The Dungeon, Orthanc, and The Game of Dungeons, all 1975 contemporaries, had thousands of eager players competing for playing time and saved game slots. We also have recollections from dozens of actual players of the PLATO games (and can, of course, play many of them ourselves right now), whereas we have only Daglow's recollections on Dungeon. I don't mean this to cast doubt on Daglow's account, just to emphasize that the PLATO games had an influence--felt directly in later commercial titles like Wizardry (1981)--that Dungeon did not, and I would thus continue to favor them as the true "first CRPGs."

The Think Series (1975-1977)

The Think series was a succession of games, or variants of the same game, with file names like Think2 and Think15. Don Gillies told me that they had been written by students of the University Laboratory High School (basically a high school run by the University of Illinois). The original was written by a Jim Mayeda. As with many of the other early RPGs, the file names were meant to disguise from university administrators the fact that the file contained a game; the lesson spaces had been created for programs to teach students about programming. The games supposedly took the grid-based gameplay of Mike Mayfield's Star Trek (1971) and ported it to a high-fantasy wilderness setting. The files were eventually deleted, but Don Gillies used the concept to write Swords and Sorcery (1978), which I covered in 2019.

DND World (1976, maybe late 1975)

DND World is another lost PLATO game written by now-retired Boeing engineer Fred Banks. Inspired by The Dungeon ("pedit5"), it took place on an outdoor map. A party of characters, controlled by a single player, explored the world, fought randomly-generated monsters, and gained in experience and treasure. Characters acted sequentially in combat. There was no winning condition. In an email to me, Banks said that the character avatars were randomly-generated, with classes and attributes following Dungeons & Dragons rules. He also said that, the overworld was "based on an octagonal circular grid, thus allowing the person to come back to the original position by walking the same direction," something that I cannot wrap my mind around. Banks did not lock the code, and other students were free to copy it and make their own modifications.

Monster Maze (1976, maybe late 1975)

Knowledge of this game came from El Explorador de RPG's research into the earliest PLATO games. For a while, it looked like it might pre-date The Dungeon on PLATO, making it the earliest known RPG. But El Explorador was able to show that the reverse as true: author Terry O'Brien created it on the CDC 6600 at Indiana University after being exposed to The Dungeon (1975; also known as "pedit5") on PLATO. The game is simplified from The Dungeon, copying the same backstory but using an all-text interface, no secret doors, no winning condition, and a slightly different spell/combat system. El Explorador was able to get access to a private server with a recreation of the game's code, and I would regard his coverage (linked above) as complete.

Pits of Baradur (1976 or 1977)

The limited information we have about Pits of Baradur mostly seems to come from a single source: a Griffith M. Morgan III, who wrote an article about the PLATO games in the Spring 2012 issue of the hobby magazine Irregular. He says that the game was created by his two friends, Justin Grunau and Michael Stecyk, and that he himself had designed one of the dungeon levels. Morgan is almost certain the same person as "Blackmoor," who provided essentially the same information on a message board in 2019, adding only that the file name was "baradur." Per recollections of a former student in the comments section below, it was apparently a top-down dungeon crawl (thus in the "pedit5" Dungeon line), "Tolkien-themed, brutally hard, not partiularly fun, and not super popular."

Bugs and Drugs (1978)

Brian Dear has a little more information about this Game of Dungeons reskin by medical students Mike Gorback and David Tanaka. It predictably used the lesson name bnd. Instead of a dungeon, the game took place in a hospital. "As you walked the corridors of the hospital, you would encounter 'monsters,' but in bnd they were bacteria or germs, and your 'weapons' to fight them were various antibiotics." Dear is the sole source on this one, but Gorback confirmed the game (without supplying any more details) in an Amazon product review. In the comments section below, former student Felix Gallo says that it was ostensibly meant to be educational.

[Edit: Bugs and Drugs turned up! My coverage starts here.]

Educational Dungeon (1979)

KARNATH (1979)

KARNATH was created on a CDC Cyber computer at the University of Minnesota by Tom Arachtingi with a friend while he was studying there, around 1979. It was a text-only multiplayer dungeon crawler game, inspired by the tabletop role-playing game The Fantasy Trip [1977]/

The dungeon was a cube of 16 levels, each with 16x16 rooms, and was randomly generated each time the person running the game started a new game. Players could chat with each other and receive automatic messages about each other's level ups or deaths.

Today the game is gone, but the main author keeps hard copies of the code and apparently tried to translate it into Java without success.

Drygulch (1980)

Drygulch is perhaps the best-documented game in this list, partly because it was developed as a commercial product. (Here I am continuing to rely on Dear's well-researched book.) In the mid-1970s, Control Data Corporation (CDC), which had been supplying hardware and software for the PLATO system for years, obtained a license from the University of Illinois to commercialize PLATO. Around 1980, the company began selling home terminals and terminal software for micro-computers, plus a service called "Homelink" that allowed home computers to connect to CDC's data center for $5 per hour.

|

| The only known photo of a Drygulch session doesn't show much, courtesy of a correspondent who took it in 1983. It depicts a desert setting with a signpost and an animal skull in the foreground. |

The service failed for a variety of reasons, but one of its outcomes was Drygulch, a western-themed MMO written by CDC employee Mike Johnson. A write-up in the November 1984 Antic magazine describes the gameplay:

PLATO's Drygulch is set in an Old West town. You are a miner trying to live long and prosper, which is not easy when hazards abound in the mines and in the wastelands surrounding the town. You must eat and drink enough to keep healthy, make sure you have enough prospecting equipment, etc. There are elections for sheriff, mayor, and mine inspector. Each position offers potential for added fun and profit.

The game featured stores, a stable, a hotel, a jail, and a cemetery. Players could play good or bad characters, and the former could bounty-hunt the latter and send them to jail. The interface contrasted a two-dimensional town with a three-dimensional mine that served in place of a dungeon, allowing players to fight enemies and return with heaps of gold.

In July 2024, I heard from a commenter named "Steve" who contributed the photograph above as well as the following additional information:

- When you first started the game, you arrived in a small mining town with just enough money to buy a few items. You needed a shovel to dig, a lantern for light, and a rope to climb between levels of the mine.

- If you stopped in a saloon for a drink, you might overhear conversation containing useful hints.

- While in the mine, other active players were depicted with line drawings.

- A mule helped you carry ore from the mine, but it cost a lot of money.

- Dead characters could be revived at the cemetery with the proper spell.

- The richest player (in a particular time period) was rewarded with the ability to change the name of the mine.

- The game changed its color settings from white-on-black to black-on-white depending on whether it was day or night.

- The game had a secret alternate town "reachable only via an unmarked, dangerous route." Very few players found it, but they got rich when they did. "The town's name was subject to change at the whim of the elected mayor."

There are elements here that remind me of both The Legend of the Red Dragon (1989) and Fallthru (1989), and I have to wonder if either author played it.

As Drygulch was played well into the mid-1980s, I can't help but think that some more photographs, if not screen shots, must still exist somewhere I don't know why Drygulch wasn't preserved by efforts like Cyber1 when they obtained the most recent CDC release.

Emprise (1980)

Another lost PLATO game to which we owe everything to El Explorador, whose research in this area has been unimpeachable: "Emprise was created on PLATO in 1980 by John T. Bryan, Laura J. Bryan, and Walter G. Brooks. It was a multiplayer dungeon crawling game with first-person graphics simulating 3 dimensions similar to, and inspired by, Avatar."

Tunnels and Trolls (1980)