My plan had been to spend March cleaning up my backlist with a quick succession of entries and finish off Angband in the background. I failed in both goals. I thought I was making progress on the list, but towards the end of the month, I checked MobyGames and found more new RPGs listed in the 1980s than I'd managed to clear. Ultimately, I've decided there's nothing to do but ignore them. I can't keep flitting around the 1980s playing pseudo-RPGs forever. I've already written about most of what's worth writing about, and the few exceptions aren't worth the rest of them. I'm still working on exactly how I'll operationalize my new plan while occasionally reaching back to the past, but that's perhaps a discussion for later.

[Ed. I didn't explain this part well. Here's what this means operationally. For the past three years, I've been alternating between games in my "current" year (the maximum year I've played) and games from the earliest year that I haven't yet played. For instance, around three years ago, I went: Star Control II (1992), Nemesis (1981), Ultizurk II (1992), The Keys of Acheron (1981), Magic Tower I (1992), Sorcerer of Siva (1981), and so forth. The problem is that earlier games keep getting discovered, so that the backlist is never fully cleared and I can never focus fully on the "current" year. What I'm working on now is a formula that gives a lot more priority to the "current" year, but that doesn't mean I'll never check out one of those earlier-year games. The ratio might just be 3:1 instead of 1:1.]

As part of my jiggering, I've done a couple other things. First, I've slightly changed my criteria for what I consider an "RPG." You can find the new definition in the FAQ. The new criteria don't really change very much, but they exclude a few games whose "character development" is largely illusory.

Finally, I'm asking you not to send me any more suggestions for additions to the list. If you care that much about a game that doesn't appear on my list, get it listed in MobyGames or Wikipedia, and I'll pick it up the next time I search those sources, which I probably won't do more than twice a year. I'm sorry if that bothers anyone, but I'm convinced that 98% of games worth playing were listed in those sources when I first started this blog 12 years ago. The quest to play every RPG that ever existed was never destined to succeed, and if I'm going to miss some games, I'd rather they were Catacombs of the Phantoms and Forest of Long Shadows instead of Fallout and Betrayal at Krondor.

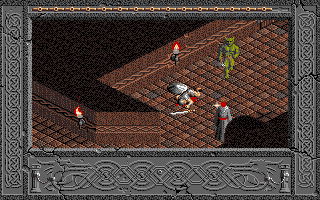

|

| I try to clear a room of giant fleas. |

That brings us to Angband. I sank another roughly 20 hours into the game during the month of March and I can't say I made a lot of substantial progress. There's no new way to express my opinion that the game is too long except perhaps to add a few obscenities, so I'll refrain from that. No I won't. The game is too goddamned long. It's too long even if you factor in the fact that some people like long games. It's too long even if you factor in the fact that I'm playing "conservatively." I can't say it any better than Jason Dyer did last week: "I find it astounding that the first variant people cranked out wasn't 'same game, but shorter.'"

It would be sensible to ask therefore why I'm still playing it. One answer that I'm tempted to give is that the character development and inventory acquisition loop is strong enough that it encourages you to keep playing. That would be a lie, though. The game certainly has a robust character development and inventory acquisition loop, but it ruins both by being--sorry for the redundancy--too long. Getting an upgrade every 30 or 40 minutes would keep me playing. In Angband, it's been more like every three hours.

Nonetheless, those aspects of the game are relatively strong, and tetrapod was right that I should talk more about inventory. It took me a while to understand what the game was doing, mostly because it doesn't start doing it in earnest until about Level 25 (out of 100). Essentially, item bonuses, materials, and effects are all variables that can be randomized--if not in any potential order, at least in a lot of them. So a random helmet might turn out to be a Steel Helmet [5, +3] of Seeing, or an axe may turn out to be an Axe [+4, +9] of Giant Slaying. As commenters pointed out, this randomization of items, materials, and effects has tabletop roots and was seen in Might and Magic III, but there it was less important because better materials far outclassed magic effects. I seem to recall that Might and Magic VI does it much better, and there it's even a bit more like Angband in that some items are named artifacts with multiple effects.

Before anyone gets too excited about this aspect of the game, however, remember that I'm playing a very early version of Angband, and I'm not sure all the effects you know and love are here. I've rarely seen anything attached to armor, for instance. But that could also be a function of the levels on which I've been operating. I suppose that's one of the reasons I've kept playing--to see how the game changes in different phases. The upshot is that I recently found a Lucerne Hammer Holy Avenger (+10, +10) [+3], with the last statistic referring to an armor class bonus. It does reasonably well.

Aside from the length, I'm disappointed in the lack of tactics compared to, say, NetHack. Maybe that changes, too, but up through my level, with my character, the only thing that seems to work consistently is to pound on enemies with my best weapon and teleport away when my hit points get too low. I have a spell for that purpose, plus a pile of scrolls to back it up when it fails. I have yet to fight a single named enemy that did not require this strategy. Missile weapons are horribly underpowered, and wands, staves, and rods that cast things like slow monster, sleep, and confusion never work against any monster that you really need them to. I'd like to experiment more with some of my cleric spells, but I need every point for "Portal" and condition-removing spells like "Remove Fear."

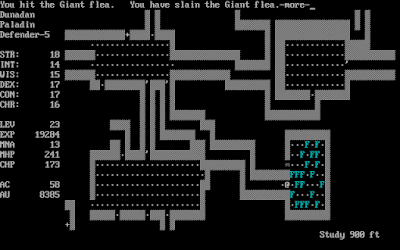

|

| Unique enemies seem to "shrug off" everything. |

Beyond that, just a lot of miscellaneous notes:

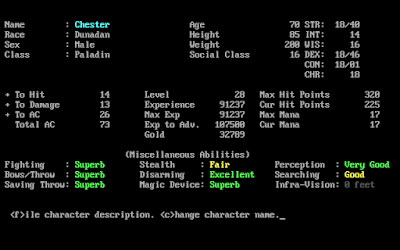

- My character is Level 28. I have no idea what the maximum character level is but the gaps have been getting longer. To get from 28 to 29, I have to earn 50% of what I've already earned in the game.

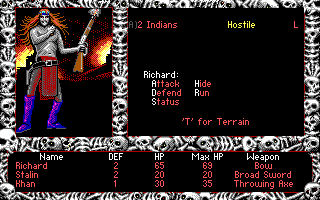

|

| My current character sheet. |

- The lowest dungeon level I've managed to reach is 31. I understand that some of you think I'm playing conservatively. I don't know what to tell you. I'm already leaving enemies I can't defeat on levels that I abandon. Also keep in mind that there are no scrolls of "Deep Diving" in this early edition.

- I've died three times, too, so if I was playing with permadeath, my "conservative" playing style would still have me on my fourth character. The most dangerous situation for me is getting blinded just as I reach the threshold where it's time to teleport away. Blinding prevents you from casting spells or reading scrolls. It doesn't prevent using wands or rods of teleport, but those haven't been common.

- Is there a common term for rooms like this? I keep encountering them on multiple levels--rectangular rooms with one entrance, packed with the same kind of enemy.

- I keep saying "teleport," but there are actually several kinds of teleportation. If I have it right, "Phase Door" moves you the shortest distance, "Portal" a medium amount, and "Teleport" to the other side of the dungeon. There are also items that "Teleport Level" to take you to an entirely different level, "Recall" you back to town, and "Teleport Other" to move a monster instead of yourself. Those last ones are effective in a pinch, but I'd rather teleport myself and know where the monster is.

- Aside from the length, the number one thing I hate about the game is having to hit ENTER to acknowledge messages in the middle of combat. Having to toggle ENTER and attack or movement keys is horribly annoying for reasons that's hard to articulate unless you've played it.

- The game is inordinately fond of packs of things, including orcs and different types of magical hounds. When you see them, you sigh because you're in for a battle against 50 of them.

- I've come to regard getting feelings like "lucky" and "super good about this level" as curses because I almost always have to abandon the levels before fully exploring them. On the few exceptions, I don't think I've typically found whatever made the level so good.

- I know they're supposed to present unique challenges, but I wouldn't mind if enemies who drain experience and enemies who corrode your items were driven out of regular RPGs. In a game as long as Angband, any reversal of a player's progress seems especially cruel.

|

| An invisible ghost drains some of my experience. |

- Perhaps the most annoying (as opposed to just difficult) enemy I've encountered so far has been magic mushroom patches. There are usually five or six of them. They attack with enormous speed, at least a couple of times in between my movements, and they cause fear, cast darkness, and blink out of existence. When you hit a patch, you get these conditions multiple times per round, sometimes requiring a dozen or more presses of the ENTER key to acknowledge all of them. Their blink ability keeps them (usually) out of melee range and their fear ability prevents you from attacking them. The only thing that's worked is to take it easy and throw items or use wands.

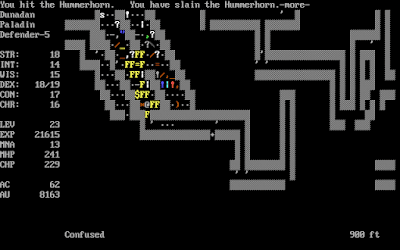

- I'm guessing rooms like the one below are the ones commenters have referred to as "vaults." I've seen them on some levels but haven't been able to loot them because of the monsters inside. This one, for instance, was full of "hummerhorns," which self-replicated faster than my ability to clear them.

|

| A "vault"? |

- Everything at these lower levels seems to be capable of causing slow, fear, confusion, or blindness, and I haven't found anything that protects against them. Most of them also seem faster than me, and I haven't found anything that increases speed.

- +10 seems to be the highest that you can enchant weapons to hit or to damage. Every scroll I've read has failed after hitting that limit.

- Potions that permanently raise your attributes are rare but a joy when you find them.

- I'm surprised at how useful "Identify" is dozens of hours into the game. A NetHack character would by now have discovered every potential item, but in Angband, the appearance of items is gated by level, so I'm still encountering scrolls, potions, wands, rods, staves, and rings that I've never seen before. I just got a Ring of Free Action for the first time as I closed this session.

- By far, the thing I appreciate most about Angband is how if you (l)ook at a monster, you get a full description of it, including its special abilities. If it's a unique enemy, you even get a little backstory. More games ought to be doing such things like this with item and monster descriptions.

|

| A description of a generic enemy. |

For the thousandth time, as I play a roguelike, I wonder why the genre had to be so light on story. Instead of useless drunks and urchins, why can't we have actual NPCs back in town, or a king who offers radiant quests like Lord British did in Akalabeth? Instead of just unique enemies on each level, why can't they be generated with little scenarios explaining their presence? Why not random encounters, perhaps with a role-playing choice, between levels? I bought Irene Gloomhaven, the board game, for her birthday this month, and she loves it. I enjoy how the city and wilderness scenarios that you draw randomly from decks give a little extra flavor in between missions. Why didn't more RPGs take that kind of approach? I like RPGs for the way that they blend mechanics and story; I rarely like one of these two elements by themselves. At least not for 40+ hours.

That seems to be a decent segue to our next game.

Time so far: 32 hours