Betrayal at Krondor

United States

Dynamix, Inc. (developer and publisher)

Released 1993 for DOS on floppy disk; re-released in 1994, 1996, and 1998 on CD-ROM, each time with different features

Date Started: 23 July 2024Date Ended: 21 January 2025

Total Hours: 72

Difficulty: Moderate (3.0/5)

Final Rating: 50

Ranking at time of posting: 501/538 (93%) Summary:

A well-written, prose-heavy sequel to Raymond Feist's Riftwar Saga, Betrayal at Krondor concerns the rise of the Moredhel (dark elves) under a new leader and their war on the Kingdom of the Isles. The player takes charge of half a dozen characters, half directly out of the Riftwar pages, as different combinations of 2 or 3 try to make sense of the invasion and the mysterious powers behind it. The game is organized into nine chapters with fixed beginning and end points, but for most of those chapters, the player is free to explore a large game world with numerous battles, encounters, treasures, and side quests.

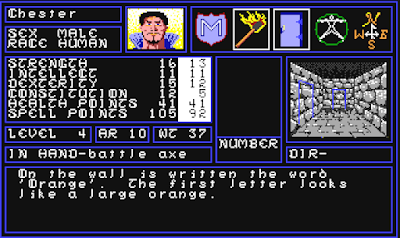

The interface is distinguished by a continuous-scrolling first-person perspective (still rare for the era), combat on a tactical grid, and an encumbrance system based on volume rather than weight. Character development occurs through the use of attributes and skills. Players have to do a lot of reading, as almost every action is narrated in paragraph form. The text is well-written but leaves little opportunity for role-playing. The plot is canon to the Riftwar franchise and was later novelized by Feist as Krondor: The Betrayal (1998).

*****

Wherever it lands on the GIMLET, Betrayal at Krondor deserves plenty of credit for offering a remarkably fresh and unusual experience. Very few things about it are individually unique, but most things about it are at least rare, and in combination they make the game unique. To list some of these factors:

- The sheer amount of text.

- The reliance on a well-established setting, and the integration of the game's story with the canon of that setting.

- Making the PCs named characters with fixed backgrounds drawn from that setting (half of them have already appeared in the books, and the rest will appear in future books).

- Using only three party members at a time.

- Having the PCs banter with each other during the adventure.

- Narrating each action as if it is a passage in a book.

|

| This is, conservatively, the 500th time that Pug has been in battle, but he still can't quite make sense of it all. |

- The use of chapters.

- An open world in many of the chapters.

- Swapping the PCs between chapters.

- A 3D perspective with continuous movement in both outdoor and indoor environments.

- Use of real people for portraits and animations.

- Combat on an isometric grid.

- Use of that same grid for non-combat trap puzzles. (In this, I think the game is unique.)

- Inventory capacity based on the physical size of objects in the pack.

We could spend hours tracing the progenitors and descendants of just a few of these elements. It's hard to imagine that New World wasn't inspired by the inventory system for Might and Magic VI, for instance, or that the authors of Krondor didn't take inspiration from Circuit's Edge or Interplay's Lord of the Rings games for plot integration. The combat perspective recalls Amberstar and Ambermoon. I swear there was some other game that narrates everything you do as paragraphs, but I can't put my finger on it.

|

| The inventory screen from Betrayal at Krondor . . . |

|

| . . . and Might and Magic VI (1998). |

Krondor unexpectedly shares some important characteristics with Star Saga, a game that I'm only wrapping up at the same time by virtue of a random roll of the dice back in December. These shared characteristics embody what I like most and least about both games. Both offer an open, nonlinear world when it comes to exploration but a tightly-scripted world when it comes to plot, including essentially no role-playing in either case. (The similarities are likely coincidental; see below.) The open world allows for great variety for the order in which players do things, or skip things, but no variety in the fundamental outcomes of the story. Krondor tells a novel-quality narrative, but it's its narrative, not the player's.

Notice that I used the term "skip" there, not "miss." To me, "miss" suggests unintentionality, perhaps even carelessness, whereas "skip" is a matter of player preference and time management. This is true even when the player doesn't know what he is skipping; if I come to a fork in the road and decide to take the left path without exploring the right path, I have "skipped" the adventures to be found down the right path, not "missed" them.

I say all of this because as we see more open worlds with side quests, optional dungeons, and skippable content, I'm going to have to make harder decisions about what I prioritize. I could have doubled the number of entries on Krondor by exhaustively exploring the world in every chapter, and I suspect some fans of the game would have preferred that. But I'm glad that I skipped some things. I'm grateful for a game that supports skipping things. I like the idea of new adventures over the horizon. I like the thought that if I ever want to come back to a game, I can enjoy a different experience. I am not a "completionist"; I reject the very term. To me, trying to experience 100% of an RPG makes as much sense as going on vacation to an unfamiliar city and insisting that I visit every street. There are too many cities that I haven't visited to spend that much time on one.

Some commenters wanted me to listen to the soundtrack. I agree that it's a superior soundtrack. I honestly could have stood to keep it going while I was playing, as it doesn't just play on an endless loop the way many games of the era do. There's a memorable title theme in 3/4 time and the cutscenes are scored with short, heavily-accented motifs. New tunes pop up during party dialogue, NPC dialogue, combat, and city title screens, but the main exploration window remains mercifully silent. The music has the appropriate tone (no hard-driving techno for this medieval RPG), has good MIDI instrumentation, and complements the game's atmosphere well. (For more, including things I didn't get to experience first-hand, see this excellent comment from Wild Juniper.) Credit goes to Jan Paul Moorhead, who we have not encountered before and will not encounter again, as Dynamix, despite its success with Krondor, never developed another RPG.

We have a lot of post-GIMLET material for this one, so let's get the GIMLET out of the way:

1. Game World. I expect Krondor to do best in this category. In well-written prose, it tells a complex, nuanced, adult plot, well-integrated with Raymond Feist's existing novels, with several fun twists. I like that there's no "evil wizard" but a group of opponents, each of which has their own reasons for their actions. For a perfect score in this category, I ask that the plot respond to the player's choices in a way reflected in the world state and NPC dialogue. That mostly doesn't happen here, primarily because there are so few choices. Everything else is solid. Score: 8.

2. Character Creation and Development. And then we have one of the weakest categories, starting with the defined nature of the characters. Is there a particular reason Owyn couldn't have been more of the player's own creation? "Development" occurs in increments as you use various skills and abilities, leading to higher numbers for the attributes and higher percentages for the skills. But those percentages are only one part of a complex formula that determines success, including equipment, fatigue, and buffing items to the point that I question whether they make all that much of a difference. I guess I'd like your opinion on that. If starting Gorath tried to finish the game with ending Gorath's equipment, would he really have that difficult a time? My skepticism here is why I never really bothered to mess around with the option to "tag" certain skills, and I don't feel like I faced a significant challenge, save for a small handful of battles.

I'll say one positive thing, here, and add a point to the score for it: I unexpectedly liked the number of party members. I found that having three members allowed me to think of each as a unique individual and not just playing a role in a "blob." Four would have been okay, too. It makes me wonder why the typical default is six. Score: 3.

3. NPC Interaction. The NPCs in Krondor are often characters from the novels. Even the ones created for this game tend to be fleshed out, with their own personalities and goals. The keyword dialogue system means that you learn a lot about the world from these NPCs. But the lack of dialogue options and role-playing in these encounters (save a very rare "Yes" or "No") option dooms the game to a middling score in this category. Score: 5.

4. Encounters and Foes. Enemies are okay. There are maybe 12-14 different types, and they do have various strengths and weaknesses that you have to adapt to. In this category, I also have to give credit for the fairy chests, the trap puzzles, and the occasional non-combat encounters that require a little imagination and creativity. The game fails to gain a point here for allowing no random battles or grinding. Score: 5.

|

| Damn. We're in a tight spot. |

5. Magic and Combat. I didn't hate the combat system but I didn't love it. I would have liked a bigger field, so that crossbows could be more relevant. I don't like how easy it was to completely obviate a spellcaster. I would have liked to see more use of terrain. The spell list contains some nice variety, but a few spells are so powerful that you could get through the game with only two or three of them. On the plus side are all of the usable objects, the relative swiftness of the experience, and the auto-combat, which works well against weak enemies. I always like spell systems that let you vary spell power, too. Score: 4.

|

| I only tried about 20% of these spells. |

6. Equipment. I like the game's inventory mechanics and the way that stores work. I like the variety of usable items. I wish there were more options for melee weapons beyond staves and swords. Armor is even worse, with only one set of "armor" (from cap to boots) and only a couple of upgrades over the course of the game. The repair system adds a little. The clear item statistics and descriptions are a nice bonus, however, and rare for the era; again, it's hard not to imagine an influence on the later Might and Magic games. I would have liked to see some randomization; according to sources I consulted post-games, the items you find on each enemy and in each chest are scripted down to the last coin. Score: 5.

7. Economy. Decent. I played too conservatively with money. Cash is useful for equipment upgrades, usable items, healing, blessing, spells, training, and teleporting, and a player who wants to run around collecting items and selling them can make about as much as he wants. It's just too bad that owing to the nature of the chapters and how the party switches between them, you're never sure if the right party is going to have the right-sized purse. It's also too bad that there are so few places to spend money during the last three chapters. Score: 5.

|

| Owyn finished the game with over 5,000 sovereigns. Even checking the purse is narrated. |

8. Quests. The game features a main quest with no player input and a nice number of side-quests and side-areas. Score: 4.

9. Graphics, Sound, and Interface. This is probably going to be controversial. I admire the graphical effort of the game. There were even times that I came upon a bridge or forest and found the scene almost pretty. The cutscene graphics for some of the towns and castles look nice. Overall, however, I thought the graphics are indicative of most of the early 1990s, when it was becoming possible to show more detail, but not yet possible for actual beauty and immersion. There were times (particularly with monster graphics) in which the developers attempted more detail than was really possible to depict, leaving a lot of confusing blobs. We've talked plenty about how the character portraits are just absurd.

There are other issues with the outdoor graphics that I didn't talk much about because I had trouble defining exactly what was wrong. There were lots of times that distances or proportions or something got screwed up, so I'd be right next to a building and not be able to see it, or there would be three chests in a cluster, but I'd only see two of them unless I left and came back from a different direction.

Sound is another matter. Not only do we get some nice sound effects, but we hear some of the only background noises of the era, with birds chirping outdoors and dripping stalactites in caves. I'll talk about music, which isn't part of the GIMLET, later.

Finally, the interface: I had no problems with the commands. The game balances the mouse and keyboard well and uses the best tool for the best job. I liked the automap and inventory screen. My only criticism comes from difficulty moving in the outdoor screens, where the corner of every mountain and river seemed to project well beyond its visible boundaries and cause the party to get hung up. Score: 5.

10. Gameplay. I still need a better name for this category. Remember, I'm looking for four things here: nonlinearity, replayability, an appropriate challenge, and good pacing. I find the nonlinearity good. It doesn't last for the whole game, but the chapters that don't feature it have good reasons. I find it only slightly replayable, owing to the things you might have skipped in the open world. The challenge was okay. The game as a whole tended towards the easy side, but some individual battles were tough. A greater part of the challenge were the quasi-survival elements such as hunger, the slow rate of healing, poison, and "near-death," all of which I liked, although in some ways the game made it a bit too easy with abundant resources.

As for pacing, I did like the variety of lengths and scopes for the chapters. No game divided into chapters should become overly predictable. At the same time, I think it was a bit too long for its content and a few of the chapters dragged a bit. Score: 6.

That gives us a final score of 50. That's in the early 90s for percentile, suggesting an A- rating. I think that works. I liked it about as much as Amberstar and Bloodstone and other games that got the same rating. I liked the story more but the mechanics less.

Krondor was widely reviewed, so we'll just take a sample. We start first with Computer Gaming World, where I am immediately irked to see a review by Jay Kee, who I've never heard of. I wanted to see Scorpia's take on this one. I guess I've become a Scorpia fan, as often as I disagree with her. Even the title annoys me: "My, But You're a Feisty One!" Ho, ho. It's a play on "Feist." But it otherwise doesn't work, since there's nothing "feisty" about the game or any of its characters. (Yes, I know, my subtitles don't always hit a home run, either. I'm not a commercial magazine with paid professional editors and 300,000 readers.) Then we have the first paragraph:

On the surface, fantasy role-playing games seem to have come a long way since the early days of text-based gaming; the days when dungeon mazes were created by bored programmers on mainframe computers. Today, the graphics, sound effects, music, and animations produced on increasingly sophisticated computers make those early efforts look like cave drawings.

Has Jay Kee ever played any of those "mainframe" games he's deriding? Because I guarantee that their programmers weren't "bored," and their outputs were anything but rudimentary. It's the earliest commercial games that look like cave drawings, not the mainframe ones. Incidentally, did an editor look at this? Because the first thing an editor does is strike "on the surface" and "seem to," and then he turns that semicolon into a dash.

Anyway, his point is to draw a contrast with the roll-your-character mechanics that have dominated CRPGs since the beginning. "Anyone expecting anything like a standard CRPG is in for a lot of surprises." And then he talks about all the things that I talked about at the beginning of this entry, except that he's convinced that Krondor heralds a new era in CRPG design, whereas I see it as a welcome variation, but not something I want to see replicated in every major RPG from now on.

I don't disagree with him on everything. He loves the open world but not the graphics. He praises the audio, the interface, and the map. But he sees the simplicity of inventory and character development as positives, which I don't, since I'm looking for an RPG rather than an adventure game. And his statement on the character portraits ("some people will not like the look of the characters or their costumes") fails to describe the depth of their inanity. Computer Gaming World would later give the game "Role-Playing Game of the Year" and name it one of the 150 best games of all time in their November 1996 issue. In August 1994, the U.S. PC Gamer ranked it 31 out of the best 40 games of all time, a rather brash article given that it was only their third issue.

I don't know why I keep going back to Dragon, which never had a good approach to reviewing computer games, but here I am reading Sandy Peterson's brief "Eye of the Monitor" column. (He starts each review with a quote from classical literature, the pretentious git, although the quote he chose, Claude Adrien Helvétius's "What makes men happy is liking what they are forced to do," is apt for this blog.) He had never read Feist, and he had trouble booting the game, so it was never destined to be a good review. He gave it 2 out of 5 stars. This paragraph is worth analyzing:

The designers, in a hare-brained attempt to make the game more realistic, have made the game hardly fun at all. You must constantly be polishing your armor, keeping your swords sharp, inspecting any food you find to make sure it's not spoiled or poisoned, replacing your crossbow's bowstrings, and continually engaging in other such dull maintenance activities.

I don't agree with him, and yet it's hard to explain why I don't agree with him. It's hard to explain why I prefer "survival" mode in games that offer it. Simply saying that I "like the challenge" doesn't seem enough. I like a variety of challenges, from the meta-challenge of finishing the game to micro-challenges like keeping my characters alive with sufficient rations. I love it when those micro-challenges sometimes come to the forefront, derailing your plans and sending you on a half-hour quest for a drink of water or a warm fire. But I suppose that's a subject for a longer entry where it's more relevant.

MobyGames's round up of reviews shows them ranging from 56% in the June 1993 German Power Play to 97% in Electronic Games. The median is about 85%, which surprises me. Overall, the various characteristics I listed at the start of this entry are present in many of the reviews, with some reviewers (incorrectly) thinking they are unique to this game, some suggesting (incorrectly) that they are heralds for CRPGs to come, and many unable to get past relatively minor parts of the game like the janky movement, the survival mechanics, and not being able to create your characters.

Given the popularity of the game, there is plenty of material to reconstruct its history. Primary sources include Neal Hallford's web site (thank you, Bronzon) and interviews with Hallford, director John Cutter, and Dynamix CEO and founder Jeff Tunnell, and Raymond Feist. The game's history was also covered thoroughly (as usual) in 2019 by the Digital Antiquarian. The original idea for Krondor was Tunnell's, who read and enjoyed the Riftwar novels. Tunnell gave the project to Cutter, who had been hired by Dynamix but was a bit adrift for his next project. (Cutter had coincidentally come from Cinemaware, which acquired the rights to Star Saga in 1990, but Cutter told me by email that he personally didn't have much to do with Star Saga and that its approach did not influence Krondor.) After securing the rights to the Midkemia setting from Feist, Cutter hired Neal Hallford, who he had met at New World, to do most of the writing. Feist had refused that role, saying, "You couldn't afford me."

Hallford had previously written the manual and in-game text for Tunnels & Trolls; Crusaders of Khazan (1990) and Planet's Edge (1991), both of which had issues but certainly gave Hallford the requisite experience. I have to agree that he really stepped up his game for Krondor. Jimmy Maher at the Digital Antiquarian says: "Hallford wrote [the game] with Feist's fans constantly in mind. He immersed himself in Feist's works to the point that he was almost able to become the novelist. The prose he created, vivid and effective within his domain, really is virtually indistinguishable from that of its inspiration," a fact no doubt responsible for persistent rumors that Feist himself wrote the game's text.

The original plan was to make a literal adaptation of Silverthorn (1985) which I agree is the most adaptable of the original novels, as it tells a relatively self-contained story in which a classing adventuring party goes through wilds and dungeons seeking a quest item. Maher's research credits Hallford for pushing for an original story instead, set during the 20-year gap in between A Darkness at Sethanon (1986) and Prince of the Blood (1989).

As we've previously discussed, the interface was adapted from a flight simulator (a genre for which Dynamix was almost exclusively known) called Aces of the Pacific (1992). It technically pre-dates, or is at least contemporaneous to, Ultima Underworld (1992) and Wolfenstein 3D (1992), although the lack of interactivity of the Krondor engine, the graphics problems, and the inability to look up and down, keeps me from taking any accolades away from those titles.

Krondor got good reviews but wasn't a smash hit financially. Maher suggests several reasons: it was over-budget and well beyond its deadline in the first place; non-Feist fans were a bit lost in the narrative; and Dynamix had the misfortune of releasing it at the beginning of a general slump in CRPG sales. Planned sequels were canceled, Cutter was fired, and Hallford quit. Nonetheless, Sierra (Dynamix's parent company since 1990) ultimately did well with CD-ROM re-releases and with interest gained by Feist's 1997 canonization of the game in novel form: Krondor: The Betrayal. (Incidentally, one of the CD versions featured this interview with Feist, where I first learned the world is pronounced "Mid-KEE-me-uh" and not "Mid-KAY-me-uh.") Although Sierra had lost the Riftwar license by then, they capitalized on the novel's release by publishing Betrayal at Antara, set in another world but using the Krondor engine, the same year. None of Krondor's principals worked on Antara.

In the meantime, a Dallas-based developer called 7th Level, Inc., purchased the rights to adapt the Riftwar setting. 7th Level commissioned a sequel, Return to Krondor, from PyroTechnix, a Cincinnati-based studio that it had acquired in 1996. In the middle of the game's development, 7th Level sold PyroTechnix—to Sierra. The game came out in 1998 and was novelized by Feist as Krondor: Tears of the Gods (2000). The literal game novelizations make up 50% of the Riftwar Legacy quartet. The other two books—Krondor: The Assassins (1999) and Jimmy and the Crawler (2013)—conclude some of the plotlines started in Betrayal at Krondor.

|

| Feist's canon novelization of the game. |

I bought The Betrayal even though I knew I wouldn't have (and haven't had) time to read it in full. I was curious how you go about adapting a game into novel form when the game already has full paragraphs of prose and basically presents itself as a novel. The results are not what I expected. Feist adheres far more closely to the plot, order of events, and even dialogue than I would have expected. He re-writes most of the prose but not in a way that makes any significant changes to facts.

The Betrayal's prologue starts a bit before the game, with Locklear hanging around Tyr-Sog, hiding from the fallout of an unwise tryst in Krondor. By Page 5, his patrol encounters Gorath fleeing a group of Moredhel eager to capture him. Locklear's party drives off the pursuers. Gorath says he has a message for Prince Arutha and refuses to give it to anyone else. The soldiers from Tyr-Sog haul him away in chains.

Chapter 1 picks up from Owyn's perspective, as he sits around a campfire and broods about what he's going to do with his life. He hears a noise, and then Locklear and Gorath come staggering into camp, Gorath having been wounded by a recent encounter with assassins. Owyn offers to help dress the Moredhel's wounds, and by Page 13, we've joined the opening moments of the game. Feist curiously uses almost none of Hallford's prose but does use a lot of his dialogue from this point. For instance, when he sees the assassin in the game, Gorath yells, "Get out from underfoot, Owyn! Assassin in the camp!" In the book, the two sentences are reversed but otherwise the same. When he gets hold of the assassin, in the game, Gorath says, "Do not struggle so, Haseth. I wish to keep you alive. But be glad I do not. The goddess of death will show you greater mercy." In the book, he says, "Do not struggle so, Haseth. For old times' sake, I will make this quick . . . May the Goddess of Darkness show you mercy."

Side quests are mostly cut. For instance, the characters hear about the Brak-Nurr in Chapter 1 but do not venture into the dwarven mines to deal with it. (They never enter the mines at all, in fact. Owyn and Gorath's journey from Krondor to Elvandar happens off-screen.) There are no rusalki in the text, no hand of glory, no Guarda Revanche. There is a mention of one "lock chest," but otherwise those fairy chests play no role in the book, nor do the copious traps, nor any NPCs who provide training in the game.

I was otherwise surprised at how closely Feist followed the plot, even when the original didn't make a lot of sense. For instance, Feist still sends the characters through the sewers on their first visit to Krondor on the silly excuse that the castle gates have been sabotaged. Owyn and Gorath's escape from Sar-Sargoth is still a bit unbelievable, although Feist does a better job justifying it by not having them engage in all kinds of noise and slaughter on the way. Perhaps most important, the characters still cover a huge amount of territory in unrealistically short time frames.

Feist does cut, expand, and recontextualize a few notable things. In the leadup to Northwarden, he skips having James and Locklear run random errands. He cuts the scene in which Arutha presides over the torture of a Moredhel captive. He introduces Makala much earlier (he's with Arutha when Locklear and company originally arrive at Krondor). [Ed. Makala is mentioned in the cutscene between Chapters 1 and 2 of the game, too. I just didn't remember.] When Gorath meets Aglaranna, he puts his hand on his sword so he can draw it and present it to her as part of the Return ritual.

Perhaps most surprising are the ways that the game seemed to change Feist's approach to the magic system of Midkemia. In the pre-Betrayal books, magic is a nebulous thing with few hard rules and not really organized into discrete, named "spells." That changes in the novelization, as in this passage where Owyn, Gorath, and Pug consider a party of Panath-Tiandn:

Gorath said, "This will be difficult, especially those two on the end with staves like yours."Owyn said, "A moredhel spellcaster named Nago tried to freeze me with a spell; I've made it work once."Pug closed his eyes and said, "I . . . I know which one you mean. The magic fetters that inflict damage. I . . . think I can cast that."Owyn said, "If we can immobilize those two, then cast a ball of fire at the rest, maybe that will cause enough panic we can get inside and find your daughter."

Feist avoids the specific spell names, but this scene otherwise feels exactly like a player planning combat tactics.

Those of you who have fully read the book, please feel free to comment with your analysis or any mistakes in my summary; again, I skimmed most of it.

This integration of a computer game with the canon of a larger franchise is groundbreaking. We've had novels based on games and games based on novels, but with Krondor we have a depth of mutual interaction that we haven't seen before, at least in the west. As such, the games paved the way for mixed-media franchises like Star Wars, The Witcher, and Fallout. Krondor isn't the highest-rated game of 1993, but for those reasons, it's a strong contender for "Game of the Year" and a worthy entry to my "Must Play" list.