|

| This title screen is from the C64 version even though I played the Apple II version. |

Warrior of Ras, Volume Four: Ziggurat

United States

Randall D. Masteller (author); Screenplay (publisher)

Released 1983 for Apple II, Atari 8-bit, and Commodore 64Randall D. Masteller (author); Screenplay (publisher)

Date Started: 12 October 2014

Date Ended: 13 October 2014

Date Ended: 13 October 2014

Total Hours: 5

Difficulty: Moderate (3/5)

Final Rating: 27

Ranking at Time of Posting: 75/164 (46%)

Final Rating: 27

Ranking at Time of Posting: 75/164 (46%)

Ranking at Game #457: 250/457 (55%)

Ziggurat brings the Warrior of Ras series to a satisfying conclusion, synthesizing elements that we saw in Dunzhin, Kaiv, and The Wylde (links to my reviews, which it would make sense to review if you want to understand this one). We've got the indoor walls and room layout of Dunzhin, the expanded item list from Kaiv, and the tactical combat system from Wylde, all in pursuit of a randomly-generated treasure, just as in the first and third games.

The back story--just as superfluous as those for the first three games--recounts a warrior's expedition to the Ziggurat of Ras, where he hoped to find the "Sapient Scepter of Sirocco" and break the power of a "wretched king whose reign of horror reduced these prosperous lands to poverty." The game's interface is presented in the manual as the creation of a magical amulet, passed down to the warrior by his father, "the great warrior Dominican." As you start your own game, you receive a random quest item--the Spiteful Rod of Jysor, the Ebony Horn of Fisat, the Silver Scarab of Sevyw, etc.--to find.

|

| The main quest is randomly generated at the start of the game. |

As with the other three, there's no character creation. You can import a saved hero from the previous games, but otherwise you start as a Level 1 adventurer with 2000 gold pieces to spend among armor, swords, torches, food, water, packs, crosses, flint & steel, ropes, dirks, picks, mirrors, and magic items. As with the previous two games, there's a magic sword for 3000 gold--something worth saving for. Unlike the previous games, you can purchase various potions, rings, and wands in the shops instead of only finding them in the dungeons. Magic dirks and magic spears also join the item list for the first time in Ziggurat. A bug in my version made dirks cost $30 but sell for $500, making it possible to get infinite gold at the outset.

|

| The market, for the first time, has potions. |

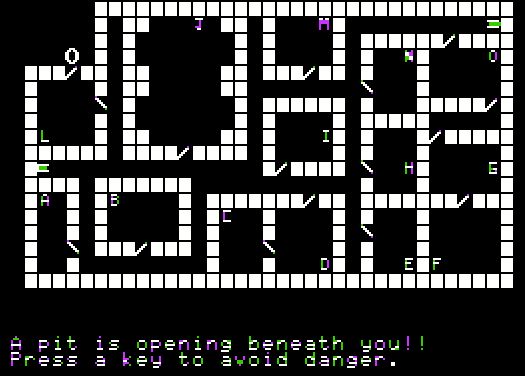

Once outfitted (the "@" gets you a "standard pack" of gear for $1900), you stash your excess treasure in the vault and then head into the dungeon. The ziggurat consists of about half a dozen randomly-generated dungeon levels connected by tunnels. As you move along, you may encounter packs of the game's varied monsters. Stepping on a special square in the rooms always generates a battle followed by a treasure haul.

In the basic interface, little has changed. You type various commands (EAT, INVENTORY, GET, MOVE EAST 3) or their abbreviations (E, I, G, M E 3) to interact with the world and your objects. Volume Four restores the ability to specify a number of squares to move that Volume 3 took away. Every so often, you have to DRINK water and EAT food to avoid hit point damage. You supposedly need torches to see, but I couldn't figure out how to light them in this game (USE didn't work), and the dungeon revealed itself despite the lack of them. I also noted that Rings of Light appeared to have no effect, so this might be something that was never sufficiently programmed. Ropes also don't appear to have any use at all.

|

| The corridor at the north end of this level is connected by two tunnels, but not to the rest of the level. |

The random events and messages that kept Dunzhin and Kaiv interesting are gone here. Ziggurat does add secret doors for the first time.

|

| You may have to walk past them a few times. |

In Dunzhin and Kaiv, combat was fought through commands on the main screen. Wylde moved this to a separate combat map, which Ziggurat preserves. I found this system admirable in Wylde--only a handful of other games in the era were offering special combat maps--but also a little annoying, as it made each combat last a bit too long. Ziggurat solves the problem by making the combat screens a lot smaller and removing navigation obstacles. I thought it hit the right balance.

Combat is governed by "turns," the number of which are affected by strength, encumbrance, and magic considerations like Potions of Haste. Every action--turning, moving, running, throwing, using a magic item, attacking--consumes a number of turns, and the character with the highest number always goes next. This is a complexity we don't see again in top-down games until maybe Wizard's Crown. Unfortunately, clever enemy pathfinding makes it hard to get on the same line with them at a distance and reduces the utility of spears and some magic items.

|

| Tossing a spear at a warrior. |

Like the previous games, in melee combat, Ziggurat allows you to do a regular HIT, AIM for a round, or put your energy into a FORCE attack, afterwards specifying what body part you want to target. Low-armored body parts like heads and necks are harder to hit but easier to score a quick kill. Each body part has its own hit points. Lucky rolls can result in critical hits that do 2 or 3 times the damage.

A few new commands make an appearance here: CHOP, GOUGE, KNEE, and KICK. Regrettably, the manual doesn't cover these new commands at all, but they seem to apply to unarmed combat.

Killing enemies gives you experience points, which in turn make up levels, which in turn affect your attack value and hit points. Leveling is rapid through Level 10 and then slows down considerably as experience point requirements increase exponentially.

|

| My character about halfway through the game. |

Magic treasures--rings, wands, and potions--are far more plentiful than in the predecessor games, at least at specific treasure squares. You can activate a Ring of Shielding, quaff a Potion of Strength or Ironskin, or wield a Wand of Fire almost every round if you want. I found that offensive rings and wands had some weird range issues--enemies can be too close to use them--but potions were particularly valuable, and I sold most of the other magic items to buy more potions of Healing, Super-Fight, and so on.

Your ultimate goal is to get strong enough to defeat the higher-level creatures on the later screens, like mummies and vampires, both of which require magical weapons to hit. One room holds the quest treasure, and I don't know if this always happens, but in my game it was in a section of a level with no doors or tunnels inside. I finally learned that you can wield a PICK and use it to knock through walls, which is how I got into the quest area.

|

| I bashed through the walls to the south and am about to pounce on the quest treasure. |

The treasure was guarded by a "zombie king," but I defeated him (aided by potions) and collected the treasure. Returning to the entrance, I was given this message:

|

| I ache to know what the rest of this message said, but I suppose it's lost to history. |

After your success, you get a new quest treasure and can keep playing the character.

The GIMLET should be, by a small margin, the highest in the series:

- 1 point for a threadbare game world.

- 2 points for character creation and development. No creation options, but leveling is rewarding.

- 0 points for no NPCs.

- 3 points for encounters and foes. No special encounters, but the monster parties have various special attacks and defenses and are well-described in the manual.

- 5 points for combat. The body part system and tactical logistics are both impressive for a 1983 game.

- 4 points for the most extensive equipment system of the series.

- 3 points for the economy, which is relevant for most of the game, especially with the ability to buy magic items.

- 2 points for having a main quest.

- 2 points for limited graphics and sound and a serviceable interface.

- 5 points for gameplay that is replayable and pitched at the right difficulty level and length.

The final score of 27 is 2 points higher than Wylde. In my post on Dunzhin, I said that the game "has some ideas too good to ignore, but it lacks too many RPG elements to fully enjoy as an RPG." It's in this sentiment that I leave the series. Although it developed some RPG elements, like an inventory system, after Dunzhin, it never really blossomed into a full-fledged RPG. On the other hand, author Randall Masteller only had a year between the first game and the last, and regardless of what I think makes a good comprehensive RPG, it's clear that Masteller achieved exactly what he set out to achieve: create a challenging game whose randomly-generated quests and dungeon levels could amuse even the game's author.

While Masteller was working on the Ras series, he was also programming and porting other authors' games for Screenplay and other companies, including MicroProse. Titles concurrent and just after Ras include Asylum II, Solo Flight, F-15 Strike Eagle, and Silent Service. More than a dozen titles follow in the 1980s, most sports and action games. He did porting work on Pirates! (1987) and Airborne Ranger (1987), both fondly remembered from my childhood. Eventually, he started his own company, Random Games, focusing on board and strategy games. You can read my full account of his work in the post on Dunzhin.

None of his future games, alas, were RPGs, so we will not be encountering Mr. Masteller again. While I can't detect direct influence of Warrior of Ras on later games, this small series represents some of the most innovative titles of the early 1980s and deserves to be better remembered. I also suspect it will be a long time before we encounter the word "ziggurat" again in an RPG.