|

| I'm not sure why this game puts its chapter number on the other side of the colon. It would make so much more sense as Star Saga One: Beyond the Boundary. |

Star Saga: One - Beyond the Boundary

United StatesMasterplay Publishing Corporation (developer and publisher)

Released 1988 for Apple II, Apple IIGS, and DOS

Date Started: 25 January 2011 (19 July 2022 for the restart)Date Ended: 25 September 2022

Total Hours: 25 (including 6 in 2011)

Difficulty: Moderate (3.0/5)

Final Rating: 31

Ranking at Time of Posting: 312/483 (65%)

The first decade and half of CRPGs saw many attempts to blend the virtual with the physical. One of the earliest commercial RPG series, Dunjonquest, provided a book of textual descriptions to accompany the player's investigations of rooms, monsters, and treasures. The Gold Box series would famously adapt this idea in its "Adventurer's Journals." But even games without numbered paragraphs often featured physical maps and physical manuals, usually with original artwork, to complete the gameplay experience. Some editions of Ultima shipped with ankhs and moonstones.

There's an extent to which these physical supplements were necessitated by technology rather than any desire to provide the player with something tactile. And certainly, when issues of storage space were all but eliminated in the mid-1990s, the tendency was to abandon anything physical--a tendency that only accelerated when players started to download their games. But I think it's a mistake to regard physical maps and manuals as something that solely existed because developers wanted to save floppy disk space for graphics and mechanics. I can't think of any game for which having a physical map to reference off-screen does not enhance the experience. As for journals and other texts, I have long been of the opinion that the computer is a better place for them since they can be informed by in-game variables (e.g., player name, sex, and choices) without requiring the publisher to have printed multiple paragraphs with only slight variations. I still feel that way, and yet I recognize that there is something exciting about the screen telling you to read Paragraph #360 in Book #6, and the player excitedly shuffling through the pages.

|

| The Star Saga games came in boxes weighing several pounds. [Photo by Ernst Krogtoft.] |

Perhaps no game offers this experience to a more intense degree than Star Saga, whose accompanying books of text run to nearly 800 pages. In a truncated 2011 review, I rejected it as a CRPG not because of the "RPG" part but because of the "C" part. While I'm not sure I entirely agree with that opinion today, I get where it came from. When 80% of your playing time is spent reading text from a book, it's hard to argue that you're really "playing." In any event, because I did play it, and numbered it, I've been carrying it as a loss for 11 years. I decided recently to remedy that. After all, I thought, how hard can it be to just read a book and report on its conclusion?

Star Saga was the creation of three Harvard University students: Rick Dutton, Walt Freitag, and Mike Massimilla. The trio started a live-action role-playing game called "Rekon" that they played once a year over long weekends. Massimilla met Andrew Greenberg, co-author of Wizardry, at a bridge tournament and invited him to join the group at their second "Rekon" weekend. Greenberg apparently felt the plot of the game had enough marketability that the group should turn it into a computer game. All four of them are credited with "game concept, design, and execution," with no separate credits for writing and programming, so I'm not sure who did what. Masterplay was created specifically for this game and its sequel, with Greenberg as president. Greenberg's old Wizardry colleagues, Roe Adams and Robert Woodhead, were two of the game's playtesters.

|

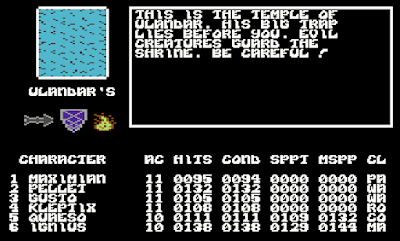

| If you played all six characters and started in 1988, I imagine you might be finishing just now. |

The broad plot of the series has elements that we've seen before in Starflight (1986) and would again in games like Star Control (1992), Planet's Edge (1992), and Mass Effect (2007), and in television like Babylon 5. Humanity is one of the galaxy's younger races. Technology may have progressed, but people are still the same. There are stories of godlike creator races who assisted the evolution of younger species. Shadows are gathering, and an ancient enemy is coming out of its slumber. But if you've heard the broad strokes before, Star Saga still does a reasonably good job with the specifics. I'm not much of a science fiction buff, so I can't say with authority that the details of the planets and races you encounter are "original," but they were original to me--and highly imaginative. The texts are reasonably well-written (bad or annoying text would absolutely destroy a game like this), and in the rare times the game strays into humor, it's situational rather than slapstick.

The game takes place in 2815, nearly 600 years after the invention of a hyperdrive made it possible to travel between stars. Humanity has colonized a local cluster called the Nine Worlds (which include "Harvard, a university planet") and other colonies throughout the galaxy. In 2490, explorers brought a "Space Plague" back to the Nine Worlds, which so decimated the home planets that humans created a great Boundary around them. Anyone can leave via the Boundary, but no one can return. A Space Patrol shoots down anyone who tries. The solution worked, but cut off from the rest of the universe, humanity has grown stagnant. Meanwhile, colonies outside the Boundary have become "Ghost Worlds," fighting for their survival while enjoying a black market smuggling trade with the Nine Worlds.

|

| My quest is laid out in a character booklet. |

Six characters have various reasons for traveling Beyond the Boundary:

- Laran Darkwatch, a disciple of the Final Church of Man, seeks a holy relic that will reveal the Final Truth

- Jean G. Clerc wants to build the Ultimate Spaceship, which will require alien technology.

- Valentine Stewart, scion of a mafia family from Wellmet, just wants to have some adventures before being chained to a desk forever.

- Corin Stoneseeker is a member of a clan that seeks the Core Stone, an artifact lost twenty generations ago.

- M. J. Turner is a Space Patrol enforcer, sent outside the Boundary as punishment.

- Professor Lee Dambroke wants to learn about alien civilizations and abilities.

Note that all of the names could be male or female, and the game goes out of its way to avoid specifying sex for many of its NPCs as well.

Once the game begins, each character has one turn to accomplish as much as possible. A turn has seven "phases," and each action takes up a certain number of phases. Moving between "trisectors" in the galaxy takes one phase. Landing on a new planet takes seven phases. Trading at the commodities market may take three or four. Learning an alien language might take 10. It's rare that you can line up exactly seven phases' worth of actions in a single turn; more likely, you go over that amount and end up borrowing phases from the next turn.

|

| In one turn, I take off from one planet, travel across four sectors, and land on another. This gives me a paragraph to read. |

You don't find out the results of each action immediately. Instead, after you've lined up everything you want to do in a turn, you execute them all at once. This is so like the approach to combat in Wizardry that I can't believe there isn't some influence. The approach creates some weird situations. For instance, you might say you want to visit the market, then blast off for another planet and maybe even travel a couple of sectors. Then, during the execution phase, something happens during your visit to the market that gives you a new option on the planet. Now you have to turn around and go back.

The computer portion of the game keeps decent track of where you are, what you've done, and what you have. (When you revisit a planet, you get a different paragraph than when you first visited.) Most of your options are usually right there on the screen. Occasionally, however, the book gives you a code for you to type in when you've met certain conditions; for instance, when you have the items necessary to assemble a particular piece of technology. Some of these codes require you to be at a particular location, but others allow you to type anywhere.

The map is clever, and I would admire it more if it weren't for my colorblindness. The galaxy is divided into 400 triangular, numbered "trisectors," each of

them blue, yellow, orange, red, green, or violet. No two triangles of

the same color are ever adjacent. Each trisector is touched by a maximum

of three other trisectors, and they all have different colors. Thus,

traveling a path through the galaxy is a simple matter of choosing a

sequence of colors to move from each trisector to the next. This works

great if you're not constantly confusing yellow with orange, orange with

red, red with green, and blue with violet. Fortunately, the game also

tells you the number of each trisector you select, and you can back out

of an option if you choose the wrong one. The map that comes with the

game has all the planets in the galaxy marked (and all of the Ghost

Worlds named); if there's ever an unmarked planet, I never found it.

Thus, unlike some space exploration games, it's relatively clear which

travel paths will bear fruit.

|

| A section of the map. To get from Bugeye to Wellmet, I would go yellow, orange, violet, blue, red, orange, blue (you have to go around the "Space Wall"). |

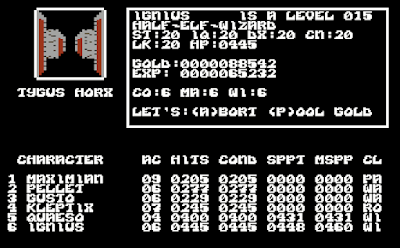

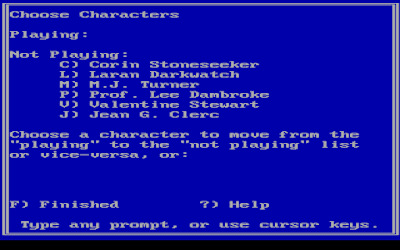

For me, by far the weirdest thing about Star Saga is the idea that it could be a group game. Up to six players can play the game at the same time, each taking a turn at the computer, but they're supposed to keep secret their experiences and the nature of their quests. The paragraphs are not read aloud. I can't imagine anything more excruciating than trying to play this game with even one other player, just sitting there as she silently reads her pages before taking my turn to do the same thing. Characters can't interact during the game except to exchange cargo, and many of the plot points don't make sense if you imagine there are multiple characters visiting each planet. [Ed. I heard directly from one of the authors, Mike Massimilla, that I misunderstood this part of the instructions. See this comment below.]

For the most part, the characters don't have unique paragraphs. Each character's visit to each planet goes about the same as any other's. Thus, one of the game's weaknesses is that you can't really "role-play" your character. The text speaks frequently in the character's voice, and the character often makes decisions within the text with no input from the player.

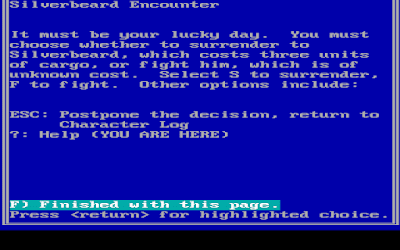

I played to the end with Corin Stoneseeker, only saving and reloading when I was ready to quit the game for the session. I rolled with a number of punches, including repeatedly losing my entire cargo hold to Silverbeard the Pirate, but I never died. The manual says death is possible, but I never experienced it. When I lost combats, the only penalties were getting kicked back to the previous stage and, occasionally, losing some cargo. The game is otherwise quite forgiving. Food and fuel exist, but only as cargo items for trade. You never have to worry about starvation, running out of fuel, or permanently damaging any of your ship's systems. Neither your character nor your ship has any hit points or damage status. Combat is entirely binary: you win or you lose.

|

| Silverbeard is a constant menace. |

When I started playing, I kept a detailed log of each turn and a summary of everything the paragraph book said. I assumed it would take a few dozen turns at most. After I crossed 100 turns, my notes became more abbreviated, and I stopped entirely after 200. I won at 378 turns. A lot of those turns simply involve flying from one place to another.

The main quests aren't all that complicated in the number of steps they require. I only experienced Corin's directly, but I got a sense of how the others would fare based on what I discovered while playing Corin. To win the game, Corin just needs to:

1. Visit Director Colmaris on Bugeye. He gives you items that belonged to your aunt, the last Core Stone seeker. They include a Flexion Glove for actually handling the stone. A note suggests that you check out the Frog Leg Nebula in Sector 133. Colmaris also gives a vague warning about something strange happening in the galaxy.

2. Fly to Wellmet, a Ghost World. Visit the tavern, where you meet a mysterious figure who gives you the "lost maps of Vanessa Chang," a famous traveler of three centuries ago. This gives you the ability to use the second, large map that comes with the game rather than the small initial one.

(These first steps are controlled by the computer. You don't get freedom to make your own choices until after the Wellmet meeting.)

3. Fly to Sector 133. There, you find an asteroid in the middle of a nebula. The asteroid hosts the wreckage of a crashed ship broadcasting a distress signal.

4. Blow the hatch to get into the ship. This is resolved as a combat.

5. Find the room from which the signal is broadcasting. You get a warning that you'll die of radiation poisoning unless you have a Super Space Suit.

6. Fly to the planet Firthe, which has an underwater civilization. Get the plans for the Super Space Suit from the aliens.

7. Collect the materials necessary to build the Super Space Suit.

8. Enter the captain's cabin in the crashed ship on the asteroid. You find the large, green, scaly, reptilian alien who stole the Core Stone from your ancestor. The stone is keeping him alive, but he's so weak with age that he can't move. You take the stone from him.

9. Return to the Nine Worlds, cross the Boundary, and fight off the Space Patrol.

10. Return to your homeworld of Atlantis. Your clan celebrates the return of the stone, but then you learn that your quest isn't over. You need to Save Humanity with the stone by visiting the place where your ancestor found it in the first place: a place called Outpost on the Arm of the galaxy. Visiting this location requires you to install a Tri-Axis Drive. Your clan gives you a key component for it.

11. Find the "recipe" for the Tri-Axis Drive on the abandoned planet of Corbis. Assemble the necessary components and build the drive.

12. Fly to Outpost, which turns out to be the pirate Silverbeard's headquarters. Defeat his defenses in a series of battles, then land at Outpost and learn the secrets of the galaxy.

|

| The game's conclusion has about seven battles in a row, each requiring different offensive and defensive equipment. |

I assume the quests for the other characters are identical starting with Step 9. This sequence may seem easy, but there are several difficult parts. First, finding the recipes for the Tri-Axis Drive and (in my case) the Super Space Suit could be difficult. I found them while randomly exploring planets. I didn't get any hints about them, but perhaps those hints exist somewhere.

Second is the problem of assembling the items that you need for your technology upgrades. Some of them are common and traded in numerous spaceports; some can be mined for free on various planets; some are extremely rare. Again, you have to visit pretty much every planet and note what resources you can find and trade there. You also have to deal with limits in your cargo hold (you get 10 bays by default) and either work within those limits or spend resources upgrading your storage space. One of the ingredients I needed for the Super Space Suit was Primordial Soup, which I found for trade on one planet, but it required like five items to trade for it.

While you're assembling all your items, you have the occasional problem of Silverbeard coming along and forcing you to surrender three cargo units or fight him and risk losing everything (he's very difficult to beat). There's a space station you can conquer to store excess items, but even that requires winning some difficult combats against its defenses first.

Finally, you have to win at least one personal combat and multiple ship combats. Both personal and ship combats are "fought" the same way. You don't really do any fighting: there are no options. Instead, you have a fixed threshold that you have to achieve for either an offensive score, a defensive score, or both. Much of the game is spent acquiring upgrades and special abilities to bolster both scores. Again, many of the upgrades require certain cargo items. You pretty much have to get all of them to win. I was repeatedly repelled by the Space Patrol while trying to revisit the Nine Worlds in Step 9, and then again repeatedly defeated by Silverbeard's defenses in Step 12, until I'd visited most of the worlds and found or purchased most of the upgrades.

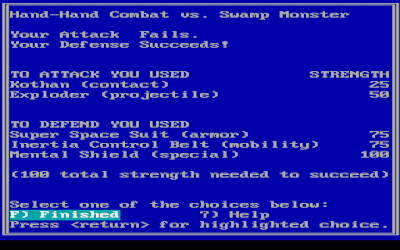

|

| A personal combat that I lost because my offensive score wasn't high enough. |

|

| A ship combat towards the end of the game that I won. |

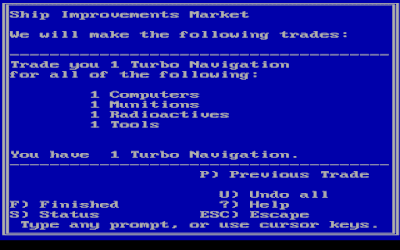

To take an example, on the planet Crater, you can purchase Boarding Robots (an offensive resource) for 1 unit of radioactives, 1 unit of medicine, and 1 unit of iron. You can mine unlimited radioactives on the asteroid in the Frog Leg Nebula and you can mine unlimited iron on Yrebe (if you've found them). Flying to both from Crater takes about eight turns. As for medicine, I never found a place where you could find unlimited amounts, but you can trade for it on Firthe if you have crystals, and you can get crystals on Jacquar for radioactives. Now I know what to do: fly to Yrebe and mine iron, then fly to the Frog Leg Nebula and mine two units of radioactives, then fly to Jacquar and trade one unit of radioactives for crystals, then fly to Firthe and trade one unit of crystals for medicine, then fly to Crater to get the upgrade. If at any time, Silverbeard appears, I have to start over. I dare say that most of the game involves flying around to assemble the right materials for one upgrade or another. The game lets you buy drone ships to do some of the trading for you (functionally allowing you to visit multiple planets' markets without having to fly there), but they themselves cost precious goods.

|

| I prepare to trade four cargo items for a Turbo Navigation system. |

The game meets my definitions of an RPG, but in weird ways. You develop your character not through regular experience or leveling but by acquiring special abilities like Telekinesis, Whurffle (a precognitive ability), Confuse Enemy Computers, and Levitation. Some of these abilities help in encounters; others help in combat. You also develop by acquiring the aforementioned offensive and defensive items. Combat does depend upon these abilities and items, and there's otherwise no randomness to combat or gameplay at all. I don't think a single moment in Star Saga depends upon the roll of a die.

The best part of playing the game is probably landing on each planet for the first time and learning what it has in store. Some of the vignettes on these planets are highly evocative and, again, original to me, though I suspect you'll tell me that some of them are drawn from famous sci-fi plots. A few choice examples:

- The planet Gironde is an industrial world populated by machines. They were put in place centuries ago by the Installer, who gave them a directive not to attempt space travel. The machines tell you that if they, or you, try to leave the planet, something called the Supervisors will attack. Sure enough, if you try to leave, you're swarmed by enemy vessels and forced to land. Through investigation, you determine that the Supervisors aren't real. Instead, every computer on the planet (including your ship's, from the moment you made contact) is infected by a virus that makes them hallucinate Supervisor ships, including mimicking the damage they would take if the Supervisors fired upon them. You have to wipe and reboot your computer to get away. You can have a discussion about all of this with the leader of the planet, called the Core, but it just raises questions about whether the fact that the Supervisors are code makes them any less "real" and whether the Core's inability to override its own programming makes it any less "sentient."

|

| A few options while fighting the Supervisors on Gironde. "Shutting down" causes the Supervisor ships to disappear, leading you to realize that they were only in the computer's imagination. |

- A planet of purple aliens called the Alkonese. Centuries ago, a race of visiting gods gave them a precognitive ability that lets them sense and avoid danger. But as "progress involves risks and sacrifices," this ability has made them lazy and self-indulgent.

- A planet with two continents, one pristine and undeveloped, the other an industrial hellscape. The latter is the home of a race of cyborgs who love where they live and regard the residents of the untouched paradise as "barbarians." I visit the barbarians and find a group of unmodified aliens who are desperate to get to the industrial continent. Apparently, an advanced race visited the planet long ago and gave them a machine called the Constructor, which can replace any biological body part with a bionic one. The machine created a caste society in which the wealthy residents partly or completely replaced their bodies and the poor ones had to remain mortal. The need to keep using the Constructor has suppressed their development of space travel. A space station orbiting the planet turns out to be the "enhanced" body of the planet's former leader.

- A human colony called Drofflic where the economy is driven by a live-action role-playing game called "Trundling." Players go through taverns, fight "monsters," and collect "treasure" under the guidance of a "cavern master." This is a clear reference to the authors and their annual "Rekon" game.

- The planet Para-Para has an underground research facility run by a shadowy military contractor whose personnel routinely sneak across the Boundary and back. There, you catch a glimpse of the man who mysteriously gave you Vanessa Chang's maps. You can have a romance here with a scientist named Dr. Peterson (no first name or sex is given). You learn that the Space Plague was bio-engineered and it was never cured; it just mysteriously stopped killing people. (It creeps me out a bit to think that in a six-player game, Dr. Peterson sleeps with every character.)

Not every planet worked for me. There's one in which the "planet" is actually the contorted body of a single creature who comes from a planet of random mutations. His mutation was to keep growing and growing beyond the ability of any planet to contain him. But even when the game shoots and misses, it never does so in a goofy way. There are moments of situational comedy, but nothing outright slapstick. Either Greenberg wasn't responsible for some of the Wizardry series' excesses or his co-authors curbed them for this project.

|

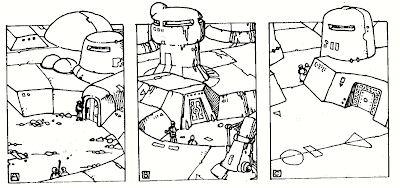

| The game rarely offers images in the booklets. Here, you're supposed to figure out which spaceport is safe to land at based on the visible condition of the port. |

There's a Big Story going on behind each character's individual quests, and I gather that it was meant to be told in a trilogy. Most of the game's exposition happens in the winning paragraphs, once you've fought your way onto Outpost, but a lot of it is hinted on individual planets, especially if you end up following the trail of Vanessa Chang.

You find Chang's ship, the Lockerbait, on Outpost. Her journal indicates that she achieved Tri-Axis technology centuries ago and used it to explore areas outside the known galaxy called the Fringe. There, they encountered a hostile race of reptilian aliens called the Clathrans. (They are clearly the same type of alien as the one who stole the Core Stone.) The Clathrans defeated, captured, and imprisoned the Lockerbait crew. The Clathrans were inexplicably repulsed by the humans, so much so that some of them had to be ordered to touch the humans even to take them prisoner. Because they were clearly out to destroy humanity, Chang's crew refused to reveal the coordinates of the Nine Worlds, even under torture. The crew eventually escaped, but was forced to leave their helmsman, John Silverbeard, behind. (He apparently escaped later, set up the defenses at Outpost to keep the Clathrans from finding Chang's ship, and then went insane and became a pirate.) The ship they stole wasn't capable of hyperspace, so they had to enter hibernation while they returned to the Nine Worlds. When they woke up and made their way slowly back home, they learned that the Space Plague--clearly the work of the Clathrans--had already devastated the home worlds. Chang came up with the plan to create the Boundary, less to prevent another Space Plague than to keep the Clathrans from finding the home worlds. She hoped that humanity would use the intervening centuries to improve its technology and be ready to face The Clathran Menace, which became the subtitle of Star Saga: Two.

Reception to Star Saga was mostly positive. In the August 1988 Computer Gaming World, William "Biff" Kritzen loved it, calling it "the most unique and well-written role-playing experience yet to appear in a computer game." He acknowledges that it would have been nice to have some combat options, but otherwise thinks that the game "stand[s] up to any human-gamemastered role-playing game on the market today," which clearly goes a bit too far. In October of the year, the magazine gave the game a "special award for literary achievement." Reviewer Gregg Keizer in the August 1988 Compute! disagrees with me, calling the game "far more a social event than a computer game" and saying that "it's lackluster without interaction." (I obviously didn't play it that way, but I still don't get it. If you follow the rules laid out in the manual, I don't see where there's much interaction.) Dragon gave it 3.5 stars in the February 1989 issue. This is low for the magazine, but the review doesn't have anything negative to say except the lack of much computer involvement in what's ostensibly a computer game.

I end my own coverage on the same sentiment. It doesn't seem to me that the authors used a computer for what a computer is good for. That someone involved in such an amazingly tactical game as Wizardry couldn't come up with a better combat system boggles the mind. Just a little probability and a few tactical choices would have enhanced the game and, even better, made better use of the technology. It seems unlikely to me that they couldn't have done it, and more likely that it simply wasn't the kind of game they were shooting for. What's left is much more "reading" than "playing." No one has posted an LP of the game on YouTube, and it would be absurd if they did.

I adjusted some of my GIMLET scores after experiencing the full game. It does best in "Game World" (7), but I was overly generous with "Character Development," "NPCs," "Encounters," "Combat" and "Equipment" the first time and ended up lowering those by a point or two. On the other hand, I was inexplicably miserly with the score of 1 that I gave to "Gameplay," particulary since the game is very nonlinear and replayable, and both the duration and difficulty are mostly on-target. I elevated the score to 6, which ended up leaving the game with its original total score of 31.

|

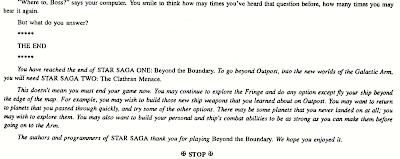

| The paragraph containing the endgame text. |

I rejected the second game without playing it, assuming it had the same

definition problems as the first. I might revisit that decision just to

see how the story continues. Unfortunately, the authors never managed to

finish the third planned game in the Star Saga trilogy, so I

assume it ends on a cliffhanger. (Low sales led Masterplay to sell the

rights in 1990 to Cinemaware, whose re-releases of the first two games sold worse than the originals.) The Internet tells me that the second game has a few more features than the first while offering about the same amount of text. It's impressive that the authors managed to write so much in just a year.

For some reason, I didn't think to review the comments to my original entry on Star Saga until after I'd finished most of this entry. It was there that I was reminded that CRPG contributor Zenic Reverie blogged about playing the game in a series of 2012-2013 entries starting here. His blog is worth reading if you want to learn more about the specific planets and paragraphs.