|

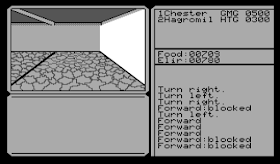

| Hey, look who's at the top of the list! |

The Game of Dungeons

United States

Independently developed in 1975 on the PLATO mainframe at the University of Illinois

PLATO lesson name dnd is sometimes given as the name of the game

Date Started: 24 February 2012

Date Ended: 25 January 2019

Total Hours: 44

Difficulty: Medium (3/5), with a lot of variance depending on playing style

Final Rating: 18

Ranking at Time of Posting: 53/316 (17%)

In preparation for taking another look at the Daniel Lawrence DND series, including Telengard, I wanted to revisit another very early PLATO RPG: The Game of Dungeons, more commonly known by its file name, dnd. It was among the first two or three computer RPGs ever created, after The Dungeon (which we just reviewed) and perhaps Orthanc.

The primary authors of The Game of Dungeons were Gary Whisenhunt and Ray Wood. The history file available on PLATO says they were inspired by The Dungeon, but other sources--including the recollections of The Dungeon's author, Reginald Rutherford--say that Rutherford created The Dungeon after programming on The Game of Dungeons had already started. Rutherford's simpler game helped fill the students' RPG cravings until The Game of Dungeons was finished later that year. The two games share a number of features, but it's not clear whether that's because The Game of Dungeons developers shared their plans with the faster Rutherford, or if Rutherford came up with the elements and inspired the later game.

Shortly after the first version of

The Game of Dungeons was released, Dirk Pellett transferred from Caltech to Iowa State University, which was connected to PLATO. He became instantly addicted to

The Game of Dungeons and sent so many suggestions for improvements to its authors that they gave him editing privileges. Later, Dirk's brother, Flint Pellett also contributed to the game. The earliest extant version on PLATO, 5.4, bears the names of Whisenhunt, Wood, and both Pellett brothers, and is dated 1977. A later version, 8.0, dates to 1978. Most of what I will discuss below relates to version 5.4, although I'll look at the other versions towards the end.

|

| An overview, written much later, by one of the original authors. |

I

covered the game only briefly back in February 2012, ultimately doubting that it was functionally possible to win it. On that point, I was later proven wrong, first by Nathan at "CRPG Adventures," who won in 2014 (coverage starts

here), then later by Ahab at "Data-Driven Gamer," who won in 2018 (coverage starts

here). In winning, both of them unearthed important facts about the game that I overlooked, and I particularly want to commend Ahab, who--in the true spirit of his blog's name--recorded hundreds of trials to determine the best spell to use against each monster and also created a full set of maps for the dungeon's 20 levels.

In fact, between the two of them, Nathan and Ahab described the game so exhaustively that this entire entry is mostly for internal comprehensiveness; I can only control and guarantee the continued availability of my own material. There's also a vanity element to it. I wanted to be able to say that I won

The Game of Dungeons despite that winning taking many hours I could have spent on other games.

In basic concept,

The Game of Dungeons isn't much different from

The Dungeon. The character--a multi-classed fighter/magic-user/cleric, with a set of

D&D-derived

attributes--enters a dungeon and starts encountering randomly-placed monsters and treasures. Against the monsters, his primary weapons are spells, and when he exhausts his spell slots, he must return to the entrance to recharge them. Returning to the entrance also converts gold to experience (in a way). Combat is generally resolved instantly, with no consideration of "rounds," and with no feedback on hits or damage. The dungeon layout is fixed, but treasure positions are randomized every time you enter (or, in the case of

The Game, change levels). There are doors and secret doors. Dungeon layout affects the chances of evading enemies in combat. Both games feature permadeath.

|

| I'm doing well here. I just arrived in the square to find $197,291 and a Level 374 demon (a "pushover" at my level). I'm above Level 1,000 and have over 12,000 hit points and a full set of magical gear. Unfortunately, this character got careless and died. |

Beyond that, there are a few differences.

The Game of Dungeons is larger, offering 20 levels of 9 x 9 to

The Dungeon's single level of 30 x 30. It has more magical objects to find (

The Dungeon just had a magic sword), but oddly fewer monsters. In the whole game, you only encounter seven of them (aside from the one dragon): deaths, demons, ghouls, men, specters, wizards, and "glass," which looks like a guy with glasses. There must have been some in-joke there.

The Dungeon capped character development very quickly, and even monsters never got higher than Level 6, while

The Game has essentially endless leveling for both monsters and the character.

The Game offers four attributes for the character--strength, dexterity, intelligence, and wisdom--and (unlike

The Dungeon) lets you re-roll if you don't like the starting values. This is worth taking some time to do because during gameplay, only strength can reliably be improved. Where

The Dungeon was often cruel in its randomization of numbers,

The Game will generally offer four values above 12 within half a dozen rolls, and within a couple of dozen, you can get all variables above 15.

|

| Attribute rolls are generous during character creation. |

Perhaps most important,

The Game is far easier than

The Dungeon, although it lasts far longer. When you play

The Dungeon, you're playing a game of luck, hoping that you can amass 20,000 experience points (probably from treasure) before something like a Level 6 ghoul shrugs off your spell and kills you in melee combat. In

The Game, by contrast, the level of monsters you encounter and their response to your attacks is almost 100% deterministic and, thus, controllable. Among your advantages:

- On Level 1 of the dungeon, you never encounter monsters higher than Level 1 themselves.

- Unless you're carrying gold, monsters will have a maximum level of roughly that dungeon level x 2.

- If you are carrying gold, monsters will have a maximum level of roughly the dungeon level x 2 plus your gold / 5000. Once you start collecting large amounts of gold, the dungeon level becomes essentially irrelevant to the difficulty of combat.

- You can drop, cache, and stop picking up gold at any time.

- Each monster has an empirically-determinable weakness to at least one cleric spell and one mage spell.

- If the monster is of equal or lower level than you, your spell will kill it almost 100% of the time.

|

| "Fight all below" is a useful command that has you automatically attack trivially-easy monsters. |

Other variables at play in the game are less sure, such as the damage you're likely to take if you fight instead of casting a spell, or the consequences of opening a treasure chest. But just with the six points above, you can carefully control your progress through the game, making it long and boring--excruciatingly so at times--but fundamentally easy. Until I figured out these rules and settled in to my final character, the number one thing to kill me was greed and impatience, usually manifested by opening treasure chests when I wasn't sure they were safe, or refusing to drop gold once acquired.

|

| Killing monsters results in a victory message like "Zzapp!," or "Swiss cheese!," or "Eat 'em alive!" |

As with The Dungeon, gold is the primary mechanism of character development here. For every 4,000 gold pieces that you take out of the dungeon, you get one more maximum hit point. Naturally, this grows slowly at first, but by the tenth hour, a single trip might add a couple thousand hit points at a time. You get another magic user spell slot for every 10,000 gold and another cleric spell slot for every 16,000, although these both cap at 25 slots, which you hit relatively early--within an hour, once you know what you're doing.

You can't ignore experience from monsters, however. It's treated separately from gold. Your experience level--which is the most important variable in combat--is defined as your current experience total divided by 10,000.

Here's where treasure chests make things insidious. When opened, they can offer

both gold and direct experience, and the values they offer are high multiples of the current dungeon level. On Level 1, for instance, loose piles of gold rarely top 50 each. Running through all 81 squares might give you 1,000 gold pieces on average. But opening a chest on Level 1 could easily give you 20,000 gold pieces, plus an equal number of experience points. Opening chests saves

hours--

days, potentially. Except that 1 in 4 will blow up and kill you, forcing you to lose all your progress.

|

| When you die, the game tells you what killed you. "The Dungeon" means that a trap killed you. |

At some point, chests stop being deadly on their levels. For instance, by about character Level 10, no chest on dungeon Level 1, even if booby-trapped, was capable of killing me outright. But because the consequences are so severe, I didn't test how this formula developed for chests below Level 1. (My best guess is that maximum damage from treasure chests is roughly the level squared x 25.) When you encounter a chest, you have an option to examine it for traps, and at least 95% of the time, your attempt is unsuccessful (the game says that it's too dark). To have any chance of reaching the end, you have to simply adopt a policy not to open such chests, as infuriating as it is to leave so much treasure and experience behind.

That's true for anything beyond the first hour, anyway. When your character is new, you might as well just open every chest you encounter and hope for the best, because a few chests can save you from going mad trying to build the character 50 gold pieces at a time. After you hit a certain level, you can still open chests on Level 1 without worry--and Level 1 chests continue to be relevant until late in the game. Even when you have 10,000 hit points and are at Level 2,000, you're not going to turn down an easy boost to either of those variables.

In fact, there's a good argument to be made for staying on Level 1 for a long time. The other magic items that you hope to find have an equal chance of appearing on any square in any level (they can also be trapped, but there's a more-reliable cleric spell to determine that), so you might as well find them in a low-risk place. Level 1 has multiple exits, the shortest only five steps from the entrance. Spending about two hours simply entering, walking down this corridor, exiting, and repeating will probably gift you with most of the game's magic items and enough treasure chests to max your spell slots and put you over Level 100. That's enough to defeat any enemy in the game as long as you're not carrying treasure.

|

| Finding a magic helm in a Level 1 corridor. Unfortunately, it's trapped. |

But you can't stay there forever. The ultimate goal of the game is to find a dragon on Level 17-20, kill it, and get its Orb. (This dragon is the first "boss" monster in any computer RPG.) That means building your character to the point that he's capable of defeating the dragon and then getting out with the Orb. When you carry the Orb, you encounter enemies in the 7-8000s; you can drop it if you're overwhelmed. We don't have enough data to know the minimum level at which success is possible or the minimum level in which it is assured, but Nathan did it at Level 6,174, Ahab did it at Level 12,440 (curiously, Ahab's maximum hit points were a lot less than Nathan's), and I did it somewhere in between at Level 8,645.

|

| This is the highest-level creature I faced in the game. |

You're not going to get to those levels by opening chests on Level 1, at least not in a reasonable lifetime, so at some point you have to start exploring downwards. This is facilitated by an "Excelsior" transport on the first level that will drop you off anywhere between Levels 2 and 20 (for a small cost in hit points). There's no similar transport on the lower levels, so you have to find your way back up. There are no stairs in the game; instead there are "transporters" that move you to a random location on a higher or lower level. These transporters, confusingly, exist between squares, not within them, and some of them are uni-directional, meaning you might move from Square 2 to Square 1 and have nothing happen, but then get transported to the next level when moving back again.

Accurate maps at this point are crucial. You always want to know the fastest way to the next "up" transporter, including places where it might be better to use a "Passwall" spell, which costs one mage slot, rather than burn six mage slots on the monsters in between. But this whole experience is only risky as long as you're carrying gold (or if you started exploring down too fast). If you just drop your gold, enemies fall to a trivial level of difficulty for a Level 100+ player.

|

| Retrieving gold from a stash. |

You thus spend most of the game heading down to a low level, gathering millions of gold pieces, and then walking back to the entrance, occasionally dumping the gold if you collect too much too fast. When you get back to Level 2, if you still have magic slots to expend, you pass time right next to the exit so that you can attract enemies and end the expedition with as much experience as possible. (Late in the game, I discovered that a good way to grind levels was to stockpile gold on Level 2 so I could attract high-level monsters there, without having to go all the way down to the bottom of the dungeon.) You do this until you feel comfortable taking on the dragon. For me, that was over a dozen hours for the final character. Two characters that preceded him, I had above Level 3,000, but I got stupid and careless in my explorations and got them killed.

(On one character, I got careless with the command that lets you automatically fight creatures below a certain level, speeding up exploration time. This command is very dangerous. For 9/10 of the game, if you set it to about 1/10 of your current level, you'll be fine. Level 1 creatures are incapable of damaging you at all once you're Level 10. The same goes for Level 10 creatures once you're Level 100. The same is

not true of Level 100 creatures when you're Level 1000. I didn't realize that all of those so-called "low-level" combats were actually sapping my hit points because the ratio had always held up before.)

|

| Here I am, one step from the transporter to Level 1, burning the rest of my mage and cleric spell slots on random encounters. |

Let's quickly cover the other items that you find in the dungeon, because they're important to understand how this game influenced the Daniel Lawrence DND line and perhaps even Rogue. As you explore, you can randomly encounter or find:

- Potions, which are sometimes poison, but this can be determined with the expenditure of a cleric spell slot. Otherwise, they're almost always beneficial, sometimes healing, sometimes restoring spell slots, sometimes granting experience, levitation, or invisibility, sometimes increasing strength by a point. One special potion, Astral Form, lets you move up and down and through walls without costing any spell points, but you can't carry gold or the Orb, so it's rarely useful except for mapping.

- Books. Reading them can increase or decrease an attribute or increase or decrease experience. They can also blow up in your face. The odds of a bad outcome seem about equal to those of a good outcome, maybe even more, and I found it was rarely worth the risk. The developers must have thought so, too, because they offered a command (SHIFT-B) to turn off book encounters; the same command doesn't exist for other types of encounters.

- Magic Swords, Helmets, Armor, and Shields, and Rings of Protection, all of which let you come out of melee combats in better shape than without them. You find the first at +1, and from there subsequent findings increase the value up to +3.

|

| Clerically examining a magic item and finding it "harmless" is one of the best things that can happen in this game. |

- Rings of Regeneration, which restore a hit point for every movement. This is useful early on, but less so later in the game when you have thousands of hit points.

- Rings of Luck, which increase your chances of finding magic items.

- Rings of Power, which add to spell power.

- Elven Boots, which reduce random encounters.

- Rings of Invisibility and Rings of Swiftness, both of which make it easier to flee random encounters.

- Rings of Levitation, which lets you walk over pits. Not a huge deal if you've been mapping carefully.

- Magic Amulets, which give you a textual assessment of the likelihood of defeating any monster you encounter, including the dragon. The assessment is based only on physical combat, however, and thus considers only your hit points and level relative to the enemy's. It does not seem to consider use of spells. Amulets also alert you when you're adjacent to a transporter.

|

| The amulet tells me "Farewell!" even though I'm almost certain to destroy him with a spell. |

- Magic Lanterns, which reveal secret doors. This treasure must be rare because only my last character found it (untrapped), and it was when he was within an hour of winning the game.

- Bags of Holding, which increase the amount of gold you can carry. Without one, you can only carry 100,000 gold pieces per point of strength; with the bag, you can carry 100 times that many. This is naturally only an issue late in the game, by which point you've almost certainly found the bag.

Once found, magic items remain with you permanently except for one case: Sometimes when a monster is about to kill you, he'll offer to spare your life in exchange for all your magic items and all your gold. Obviously, careful planning avoids such situations. But it's still better than starting over.

It's also worth looking at the spells. Unlike

The Dungeon, you have access to all of them at the outset, and all of them require a single spell slot. (The one exception is the non-combat "Teleport" spell, which moves you up a level for 2 mage slots and 1 cleric slot. It fails 10% of the time, so it's best not to rely on it.) Most of them are derived from

Dungeons & Dragons and were featured in

The Dungeon. (It's also worth noting, if only for later reference, that the command used in both games is "Throw Spell.") They include the mage spells "Fireball," "Lightning," "Flaming Arrow," "Sleep," and "Charm," and the cleric spells "Holy Water," "Exorcise," "Pray," and "Dispell."

|

| Casting a spell against a wizard. "Lightning Bolt" almost always kills them, but it can ricochet and hit you, too. |

A couple of them are oddly named, including mage spells called "Kitchen Sink" and "Eye of Newt" and a humorous clerical counterpart to "Dispell" called "Datspell." None of these spells are described, so you simply have to imagine how they're affecting the enemies.

As I mentioned earlier, the weaknesses and resistances of the seven enemies to these spells are so stark that they're almost deterministic. Ahab did an excellent job

analyzing it on his site, including a few variables I'm glossing over. Each enemy has at least one mage spell and one cleric spell that works 100% of the time. This doesn't mean that it will necessarily kill the enemy, and if it doesn't, you have to follow up with a melee round. But it

will kill an enemy of equal level (not counting modifiers based on equipment) about 100% of the time, and the enemy level, as above, is essentially a variable that you can control.

|

| "Flaming Arrow" inevitably works on spectres, but they're immune to "Lightning Bolt." |

On top of the 6 hours I spent on the game in 2012, it took me another 6 to internalize all the above. I burned 20 hours on two characters who ultimately died (and nearly gave up this whole enterprise), and another 12 on my final character. Once I crossed experience Level 8,000, I decided I was strong enough for the dragon plus all the enemies who attack you when you have the Orb. (The dragon moves around Levels 17-20 during the course of the game. If you encounter him before you're ready, you can evade with 100% success.) There's a spell that destroys the dragon, but it costs almost all of your spell slots and is thus not worth it. Like Nathan and Ahab before me, I depleted him with "Lightning Bolt" and finished him off in melee combat.

|

| Just after I killed the dragon. |

After that, I just had to make my way back to Level 1 and then the exit. My name finally appeared on the list of "Finders of the Orb," another element that we'll want to preserve in memory for later.

As I've mentioned before, it's silly to emphasize the GIMLET on these

early games. I gave it a 15 when I first played it in 2012. Reviewing

the categories now, I think I was too stingy on combat, equipment, and

the economy, and I bumped each of those up a point for a new final score

of 18.

|

| Getting this screen was quite a relief. |

I played version 5.4, which dates from 1977, after the Pelletts' influence. I haven't been able to find much information on version 1, but it apparently only had two magic items--a shield and sword. It also had so few character slots that the developers had to create an algorithm for prioritizing what active characters to purge to make room for new ones.

Version 6.0, dating from the same year, had mostly minor updates. Attributes govern more than they did in 5.4; for instance, intelligence and wisdom affect both starting and maximum magic-user and cleric spell slots, respectively. Additional monsters appear--including rust monsters, mind flayers, vampires, and balrogs--and many of them have special attacks and effects. There are also new magic items, including gauntlets, wands, and horns. There's a new option in combat to use some of these items. The most important difference is that gold adds directly to experience, which governs spell acquisition, leveling, and hit points; you no longer earn experience separately from gold.

There's no documentation on Version 7, but Version 8 (1978) has some significant changes. (Nathan has excellent coverage of Version 8, starting

here. It took him a year of on-and-off playing to win.) First, there are three dungeons to choose from: the original Whisenwood, The Caverns, and the Tomb of Doom. The same character can bounce among them. At the top, there's a couple of shops. Whisenwood no longer has a main quest; it exists just for character development, plus a healing fountain at the bottom level that can raise attributes. The Caverns have the Orb and the dragon. The Tomb of Doom has the Grail, guarded by a vampire. Players have to find both the Orb and the Grail to enter the Hall of Fame--or simply achieve character level 1000. There are now four races--human, elf, dwarf, and gnome--to choose, as well as 20 Orders to join. Endurance appears as an attribute. Experience rewards and leveling are significantly scaled back. New monsters include Eyes of Thieving, which steal your stuff, and various types of slimes, which have all kinds of interesting effects. You can charm monsters to follow and fight for you. Robes, crosses, books, and lamps join the equipment list, and potion effects are expanded to include improvements to

all attributes, Treasure Finding, Hallucination, and Fire Resistance. Each character begins with a random "inheritance," which is usually a magic item. We're only half a step from roguelikes at this point.

As we've seen in previous postings, The Game of Dungeons directly influenced Daniel Lawrence and his DND/Telengard line (no matter what Lawrence himself may have said), and from there a number of other descendants like Bill Knight's DND (1984) and Caverns of Zoarre (1984). There are also a couple of games that sprout directly from The Game without going through Lawrence, including Dungeon of Death (1979) and The Standing Stones (1983). I'd also suspect that version 8 influenced Rogue except that I can't find any evidence that Michael Toy and Glenn Wichman had any exposure to PLATO way out in California.

Tracing the elements of each game can help us determine the appropriate family tree, and to that end, we're indebted to

a table that Ahab began in an attempt to track these elements. For instance, it's pretty absurd for Lawrence to say that he wasn't influenced by

The Game when his original

DND has an "Excelsior" transport and a list of winners titled "Finders of the Orb" (as well as the same basic gameplay, of course). Similarly, separate options to "open" and "carefully open" treasure chests help trace a line directly between

The Game and Gordon Walton's

Dungeon of Death.

|

| Based on evidence so far, I'm pretty sure this is the correct family tree. But I'll edit as necessary. The one major problem is that the 1976/1977 "DND" is actually several versions on several platforms across several years. |

Thanks to Nathan and Ahab prompting me to spend more time with The Game of Dungeons, I feel that I understand this early, seminal RPG a lot better. Later, we'll take a closer look at Daniel Lawrence's original DND and the debt it owes to The Game.